Cloud generations drive down prices

Cloud providers need to deliver the newest capability to stay relevant. Few enterprises will accept working with outdated technology just because it’s consumable as a cloud service. However, existing cloud instances don’t migrate automatically. Similarly to on-premises server infrastructure, users need to refresh their cloud services regularly.

Typically, cloud operators prefer product continuity between generations, often creating nearly identical instances. A virtual instance has a “family”, which dictates the physical server’s profile, such as more computing power or faster memory. A “size” dictates the amount of memory, virtual processors, disks and other attributes assigned to the virtual instance. The launch of a new generation usually consists of a range of virtual instances with similar definitions of family and size as the previous generation. The major difference is the underlying server hardware’s technology.

A new generation doesn’t replace an older version. The older generation is still available to purchase. The user can migrate their workloads to the newer generation if they wish, but it is their responsibility to do so. By supporting older generations, the cloud provider is seen to be allowing the user to upgrade at their own pace. The provider doesn’t want to appear to be forcing the user into migrating applications that might not be compatible with the newer server platforms.

More generations create more complexity for users through greater choice and different virtual instance generations to manage. More recently, cloud operators have started to offer different processor architectures in the same generation. Users can now pick between Intel, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) or, in Amazon Web Service’s (AWS’s) case, servers using ARM-based processors. The variety of cloud processor architectures is likely to expand over the coming years.

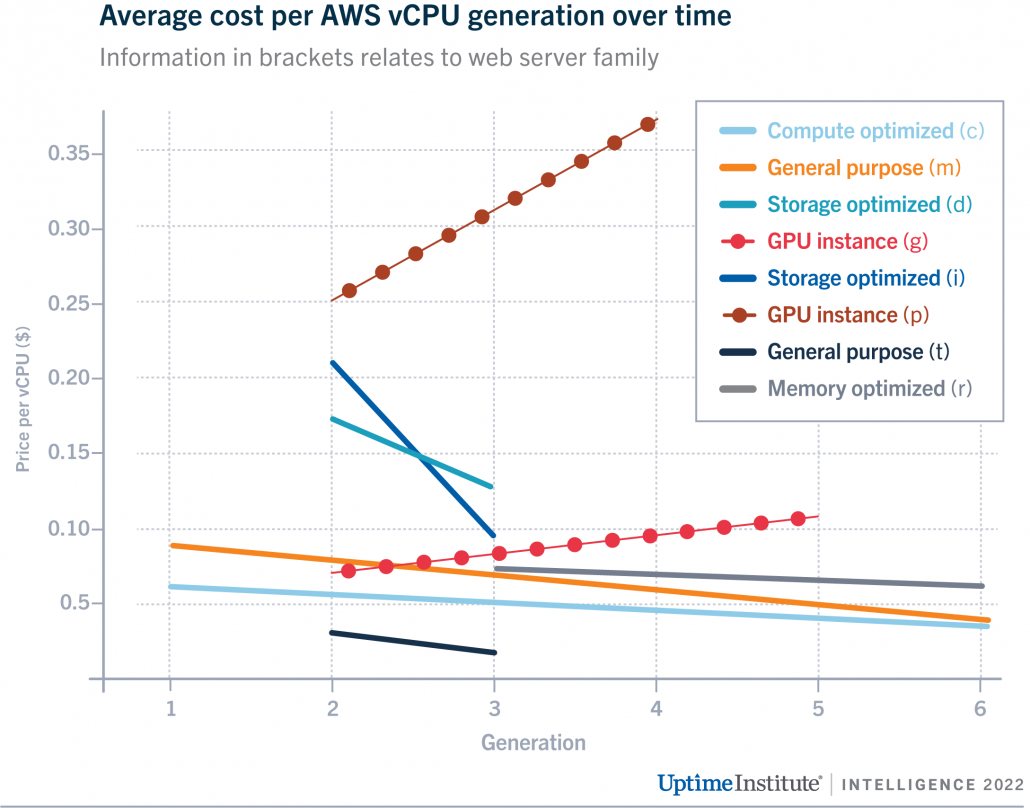

Cloud operators provide price incentives so that users gravitate towards newer generations (and between server architectures). Figure 1 shows lines of best fit for the average cost per virtual central processing unit (vCPU, essentially a physical processor thread as most processor cores run two threads simultaneously) of a range of AWS virtual instances over time. Data is obtained from AWS’s Price List API. For clarity, we only show pricing for AWS’ US-East-1 region, but the observations are similar across all regions. The analysis only considers x86 processors from AMD and Intel.

The trend for most virtual instances is downward, with the average cost of the m family general-purpose virtual instances dropping 50% from its first generation to the present time. Each family has different configurations of memory, network and other attributes that aren’t accounted for in the price of an individual vCPU, which explains the price differences between families.

One hidden factor is that compute power per vCPU also increases over generations — often incrementally. This is because more advanced manufacturing technologies tend to help with both clock speeds (frequency) and the “smartness” of processor cores in executing codes faster. Users can expect greater processing speed with newer generations compared with older versions while paying less. The cost efficiency gap is more substantial than simple pricing suggests.

AWS (and other cloud operators) are reaping the economic benefits of Moore’s law in a steep downward trajectory for cost of performance and passing some of this saving onto customers. Giving customers lower prices works in AWS’s favor by incentivizing customers to move to newer server platforms that are often more energy efficient and can carry more customer workloads — generating greater revenue and gross margin. However, how much of the cost savings AWS is passing on to its customers versus adding to its gross margin remains hidden from view. In terms of demand, cloud customers prioritize cost over performance for most of their applications and, partly because of this price pressure, cloud virtual instances are coming down in price.

The trend of lower costs and higher clock speed fails for one type of instance: graphics processing units (GPUs). GPU instances of families g and p have higher prices per vCPU over time, while g instances also have a lower CPU clock speed. This is not comparable with the non-GPU instances because GPUs are typically not broken down into standard units of capacity, such as a vCPU. Instead, customers tend to have (and want) access to the full resources of a GPU instance for their accelerated applications. Here, the rapid growth in total performance and the high value of the customer applications (for example, training of deep neural networks or massively parallel large computational problems) that use them allowed cloud operators (and their chip suppliers, chiefly NVIDIA) to raise prices. In other words, customers are willing to pay more for newer GPU instances if they deliver value in being able to solve complex problems quicker.

On average, virtual instances (at AWS at least) are coming down in price with every new generation, while clock speed is increasing. However, users need to migrate their workloads from older generations to newer ones to take advantage of lower costs and better performance. Cloud users must keep track of new virtual instances and plan how and when to migrate. The migration of workloads from older to newer generations is a business risk that requires a balanced approach. There may be unexpected issues of interoperability or downtime while the migration takes place — maintaining an ability to revert to the original configuration is key. Just as users plan server refreshes, they need to make virtual instance refreshes part of their ongoing maintenance.

Cloud providers will continue to automate, negotiate and innovate to drive costs lower across their entire operations, of which processors constitute a small but vital part. They will continue to offer new generations, families and sizes so buyers have access to the latest technology at a competitive price. The likelihood is that new generations will continue the trend of being cheaper than the last — by just enough to attract increasing numbers of applications to the cloud, while maintaining (or even improving) the operator’s future gross margins.

UI 2020

UI 2020

2020

2020