Industry consensus on sustainability looks fragile

Pressed by a sense of urgency among scientists and the wider public, and by governments and investors who must fulfil promises made at COP (Conference of the Parties) summits, major businesses are facing ever more stringent sustainability reporting requirements. Big energy users, such as data centers, are in the firing line.

Many of the reporting requirements, and proposed methods of reducing carbon emissions, are proving to be complicated and may appear contradictory and counterproductive. Many managers will be bewildered and frustrated.

To date, most of the commitments on climate change made by the digital infrastructure sector have been voluntary. This has allowed a certain laxity in the definitions, targets and terminology used — and in the level of scrutiny applied. But these are all set to be tested: reporting requirements will increasingly become mandatory, either by law or because of commercial pressures. Failure to publish data or meet targets will carry penalties or have other negative consequences.

The European Union (EU) is the flag bearer in what is likely to be a wave of legislation spreading around the world. Its much-strengthened Energy Efficiency Directive, part of its “fit for 55” initiative (a legislative package to help meet the target of a 55% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030), is but one example. This legislation will require much more granular and open reporting, with even smaller-sized data centers (around 300–400 kilowatt total load) likely to face public audits for energy efficiency.

For operators in each part of the critical digital infrastructure sector, there may be some difficult decisions and trade-offs to make. Cloud companies, enterprises and colocation companies all want to halt climate change, but each has its own perspective and interests to protect.

Cloud suppliers and some of the bigger colocation providers, for example, are lobbying against some of the EU’s proposed reporting rules. Most of these organizations are already highly energy efficient and, by using matching and offsets, claim a very high degree of renewable use. Almost all also publish power usage effectiveness (PUE) data and some produce high-level carbon calculators for clients. Significant, step-change improvements would be complex and costly. Additionally, they argue, a bigger part of the sector’s energy waste takes place in smaller data centers, which may not have to fully report their energy use or carbon emissions — and may not be audited.

Colocation companies have a particular conundrum. Their energy consumption is high profile and huge — and clients now expect their colocation companies to use electricity from low-carbon or renewable sources. But this requires the purchase of ever more expensive RECs (renewable energy certificates), also known as Guarantees of Origin, and / or expensive, risky PPAs (power purchase agreements).

Purchasing carbon offsets or sourcing renewable power alone, however, is not likely to be enough in the years ahead. Regulators and investors will want to see annual improvements in energy efficiency or in reductions in energy use and carbon emissions.

For a colocation provider, achieving significant energy efficiency gains every year may not be possible. More than 70% of their energy use is tied to (and controlled by) their IT customers — many of whom are also pushing for more resiliency, which usually uses more energy. This can also apply to bare metal cloud customers.

In most data centers, the IT systems consume the most power and are operated wastefully. To encourage more energy efficiency at colocation sites, it makes sense for enterprises to take direct, Scope 2 responsibility for the carbon associated with the purchased electricity powering their systems. At present, most enterprises in a colocation site categorize the carbon associated with their IT as embedded Scope 3, which has weaker oversight and is not usually covered by expensive carbon offsets.

While many (including Uptime Institute) advocate that IT owners and operators take Scope 2 responsibility, it is clearly problematic. The owners and operators of the IT would have to be accountable for the carbon emissions resulting from the energy purchases made by their colocation or cloud companies — something many will not yet be ready to do. And, if they are responsible for the carbon emissions, they may have to also take on more responsibility for the expensive RECs and PPAs. This may be onerous – although the change might, at least, encourage IT owners to take on the considerable task of improving IT efficiency.

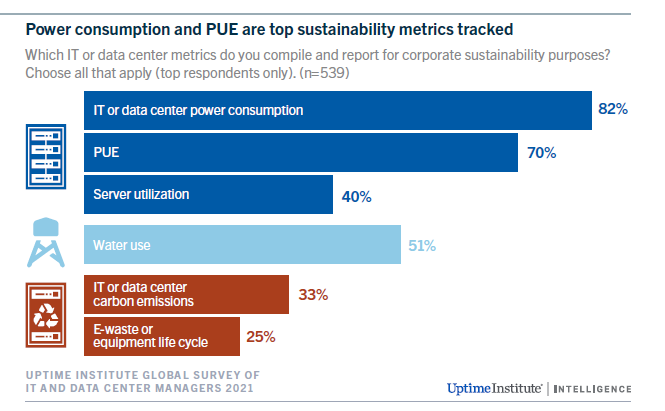

IT energy waste is a challenge for most in the digital critical infrastructure sector. After a decade of trying, the industry has yet to settle on metrics for measuring IT efficiency, although there are good measurements available for utilization and server efficiency (see Figure 1). In 2022, this challenge will rise up the agenda as stakeholders once again seek to define and apply the elusive metric of “useful work per watt” of IT. There won’t be any early resolution, though: these metrics are specific to each application, limiting their usefulness to regulators or overseers — and executives may fear the results will be alarmingly revealing.

The full report Five data center predictions for 2022 is available to Uptime Institute members here.

2019, Getty

2019, Getty

Getty

Getty