COVID-19: Critical impact and legacy

What will be the long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the digital critical infrastructure industry? It may be too soon to ask the question given that, at the time of writing, the virus is taking its toll at scale across the world. But Uptime Institute has been asked this question many times, and it’s a discussion point on several upcoming (virtual) conferences.

In a recent Financial Times column, the economist Tim Harford speaks of “hysteresis” — a concept borrowed originally from electromagnetics. Hysteresis describes how some events have a long-lasting, lagging impact, even after the original cause of the change has long gone. Some of the effects of the coronavirus pandemic are elastic — industries, behaviors and business models, for example, are pulled around, but they will spring back their original shape as the risk passes. But others behave more like plastic: once stretched or broken, they stay that way.

While it may be soon to tell, many businesses and investors have already begun making bets that certain things have changed forever. Some companies are preparing for the sale of the headquarters; several have told their staff that, from now on, they are at-home workers. One conference company has moved its entire business online. And in the critical infrastructure world, we know of companies that have already begun to introduce permanent changes in the data center, including introducing large-scale automation programs (to reduce the need for on-site staff).

Uptime Institute has classed the evolution of the digital critical response into three phases.

Phase 1

The first phase might be termed “reactive.” At this point, operators are on high alert, in firefighting or emergency response mode. Their biggest concerns are to understand the threat and to identify and implement best practices to decrease the risk to staff and to availability; high on the list are the need to source appropriate personal protective equipment and decontaminants, to clean facilities, and to operate with reduced staff and possible supply chain disruption. For most, this phase lasted a few weeks or more and has already passed. While the vast majority came through this well, about one in 20 data centers told Uptime Institute in a survey that they had a COVID-19 related outage. Others said they experienced IT service slowdowns, likely due to changing demand patterns or server/network maintenance problems.

Phase 2

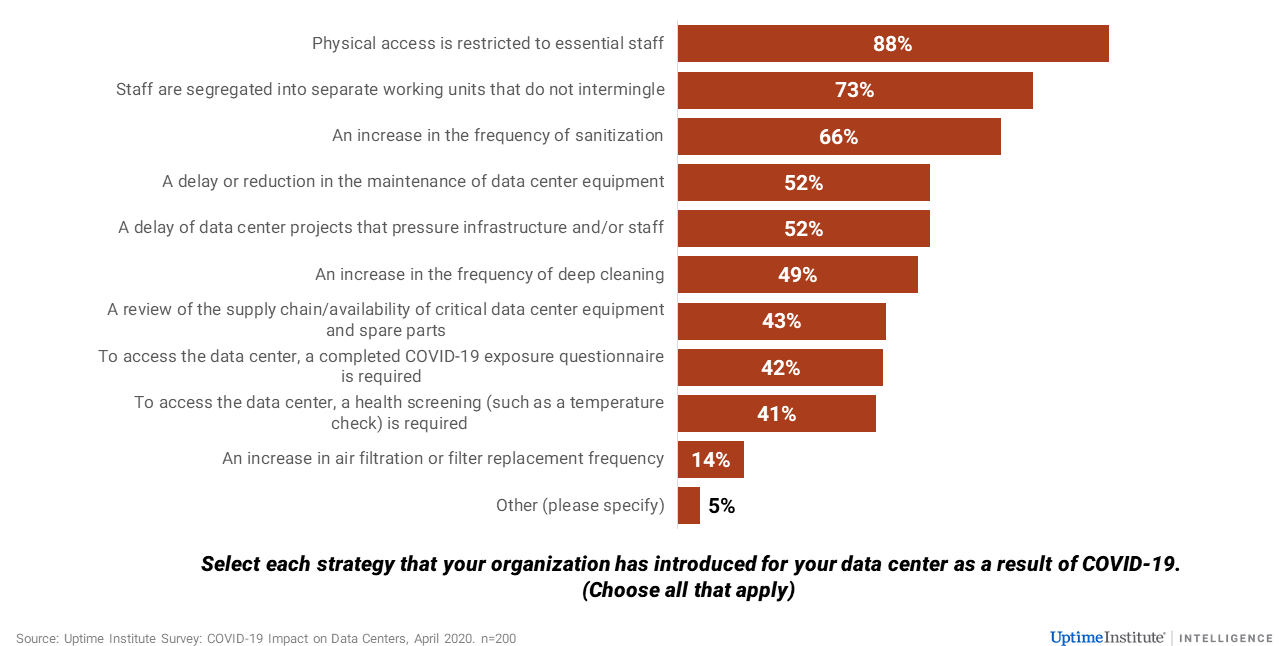

The second phase is an interim normal – most data center operators are in this period (which may last up to a year). In this phase, the virus is still widespread, but threat is reduced as governments regain control of the spread. Processes to manage-down risk that were established in the reactive phase have become established — these include more remote working, blue/red operations teams, reduced maintenance, greater redundancy, and now form the “new normal.” Most of these are process-based and do not involve long-term investments or strategic changes. Some examples of these activities are presented in the chart below.

During this phase, delayed projects are likely to be gradually restarted, but only as a managed risk; investment is curtailed unless clearly pulled by strong demand (which continues to drive new builds and investments). At this time, the management also prepares investment projects for the third phase — the next permanent normal.

Phase 3

The third stage of this cycle is the next normal. At this point, it is likely a vaccine has been found, treatments have improved, or the virus has been contained by social measures to the point of routine manageability. However, the world has been alerted to the possibility (likelihood?) of another pandemic — so long-term changes are likely, alongside the acceptance of other changes that were found to have proved effective, in spite of the danger’s having passed.

What will these be? Here, the answers are less clear. We think the following are highly likely:

- Operators will incorporate pandemic planning (and drilling) into their business continuity/disaster recovery plans.

- Governments will seek to have more insight and oversight of critical and near-critical infrastructure, including establishing key worker principles, etc. This may involve more certification.

- Automation/remote management tools will receive a surge of investment, as operators seek to operate with fewer staff/no staff at times, or to monitor systems from safer or remote locations.

- Greater management of the supply chain for key parts or services. This is likely to drive budgets up, especially if emergency cover agreements need to be put in place with services companies.

Here are some other possible developments, where the outcome is less clear:

- A greater/faster move to cloud. This may happen, but this is a trend two decades old, and existing critical loads are being moved steadily and slowly, not rapidly. In addition, cloud may require increased, not decreased, funding.

- A shift to edge. More home working, viewed by many as a trend that won’t be reversed, will lead to more work being done away from corporate offices and at edge locations.

- A need for more staff. In spite of planned automation, data centers will, in the near term (to 2023?), need more staff to fulfill the requirement of maintaining separate teams.

One thing all analysts agree on: The pandemic has not slowed, and has probably accelerated. This has raised both the demand for more data center services and the dependency on these services yet further.

UI 2020

UI 2020

Uptime Institute, 2019

Uptime Institute, 2019

2019

2019

2020

2020