Empowering the Data Center Professional

Five questions to ask yourself, and five to ask your team

By Fred Dickerman

When Uptime Institute invited me to present at Symposium this year, I noticed that the event theme was Empowering the Data Center Professional. Furthermore, I noted that Uptime Institute described the Symposium as “providing attendees with the information to make better decisions for their organizations, and their careers.” The word empowering really caught my attention, and I decided to use the session to discuss empowerment with a peer group of data center professionals. The results were interesting.

If you manage people, chances are you have spent some time asking yourself about empowerment. You may not have used that word, but you would have certainly asked yourself how to make your people more productive, boost morale, develop your people, or address some other issue, which can be related back to empowering people.

If you don’t manage people but there is someone who manages you, you’ve probably thought about some of these issues in relationship to your job. You may have read books on the subject; there are a lot of books out there. You may have gone to the internet; I recently got 5,000,000 results from a Google search on the word empowerment. And many of us have attended at least one seminar on the subject of empowerment, leadership, motivation, or coaching. Empowerment Fire Walk is my favorite such title.

Even so, the act of empowering people is a hit-or-miss activity.

In 1985, the author and management consultant Edward deBono, perhaps best know for originating the concept of lateral thinking, wrote the book Six Thinking Hats (see the sidebar). In that book, DeBono presented an approach to discussion, problem solving, and group interactions, in which he describes six imaginary hats to represent the six possible ways of approaching a question.

The green hat, for instance, focuses on creativity, possibilities, alternatives, and new ideas. It’s an opportunity to express new concepts and new perceptions.

Let’s put our green hats firmly in place to examine the issue of empowerment. We can start by creating a distinction between two different types of questions. The first questions are the everyday questions, such as “Where should we go for lunch?, which UPS system provides the best value for investment?, and should we build our own data center or lease?” We value the answers to these questions. Everyday questions can be trivial or very important, with big consequences sometimes resting on the answers.

We derive value from answers to the other question type but also from the question itself. We can call these questions inquiries.

Focus is the difference between everyday questions and inquiries. The answer is the focus of the everyday question. Once we have an answer to an everyday question, we tend to forget the question altogether and base our next actions on the answer. After the question is forgotten, other possible answers are also forgotten.

On the other hand, if you are engaged in an inquiry, you continue to focus on the question—even after you have an answer. The inquiry leads to other answers and tests the answers you have developed. The inquiry continues to focus on the question. As Isaac Newton said, “I keep the subject of my inquiry constantly before me, and wait till the first dawning opens gradually, by little and little, into a full and clear light.”

In addition to having more than one answer (and usually no single right answer), other characteristics of the inquiry are:

• The answers rarely come easily or quickly

• The questions tend to be uncomfortable

• Answers to the initial question often lead to other questions

Thorstein Veblen said, “The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.”

Our question, “How do you empower people,” pretty clearly falls into the category of inquiry. Before we start to propose some of the answers to our empowerment inquiry, let’s introduce one more idea.

An Example

What is the difference between knowing how to ride a bicycle and being able to ride a bicycle? If you were like most children, you probably first decided to learn to ride a bicycle. Then you probably gathered some information, perhaps you read an article on how to ride a bicycle watched other people ride bicycles, or had a parent who helped.

After gathering information, you may have felt ready to ride a bicycle, but if you were speaking more precisely, you could really only claim to know how to ride a bicycle in theory. Then, you got on the bicycle for the first time and fell off. And, if your focus during that first attempt was on the instructions you obtained from your parents or other expert source, you were almost certain to fall off the first few times. Eventually, with patience and commitment, you finally learned how to ride the bicycle without falling off.

First, once you have ridden the bicycle, you will probably always be able to ride a bicycle. We use the phrase “like riding a bicycle” to describe any skill or ability which, once learned, seems to never be forgotten.

Second, if you were trying to teach someone else how to ride a bicycle, you probably could not find the words to convey what happens when you learn how to balance on the bicycle and ride it. In other words, even though you have successfully been able to ride the bicycle, it is very unlikely that you will be able to add anything useful to the instructions you obtained.

Third, making that shift from knowing how to being able to is likely to be unique to the basic skill of riding the bicycle. That is, learning to ride backward, on one wheel, or without holding the handlebars will require repeating the same process of trying and failing.

The hundreds or thousands of books, seminars, and experts providing knowledge on how to empower people cannot teach anyone the skill of empowering others. When you have empowered someone, you probably will not be able to put into words what you did to produce that result, at least not so that a person reading or hearing those words will gain the ability to empower others.

The ability to empower is probably not transferable. Empowering someone in different circumstances will require repeating the learning process.

You can probably see that this article is not going to teach you how to empower people. But if you are committed to empowering people and are willing to fall off the bicycle a few times, you will have new questions to ask.

Giving Power

The best way to empower someone is to give them power, which is easy if you are royalty. In medieval times, when monarchs had almost unlimited power, the empowerment was also very real and required only a prescribed ceremony to transfer power to the person.

Not surprisingly, the first step to empowering others still requires transferring official authority or power.

Managers today wrestle with how much authority and autonomy to give to others. In an article entitled “Management Time, Who’s Got the Monkey?” (Harvard Business Review, Nov.-Dec. 1974, reprint #99609), William Oncken and Donald Wass describe a new manager who realizes that the way he manages his employees does not empower them.

Every time one of the employees would bring a problem to the manager’s attention, the way the employee communicated the problem (in Oncken’s analogy a “monkey”) and the manager’s response to the problem would cause the problem to become the manager’s responsibility. Recognizing the pattern enabled the manager to change the way he interacted with his employees. He stopped taking ownership of the problems, instead supporting their efforts to resolve the problems by themselves. While Oncken and Wass focus mainly on time management for managers, the authors also deal with the eternal question for managers of delegation of authority, with five levels of delegation from subordinate waits to be told what to do (minimal delegation) to subordinate acts on his own initiative and reports at set intervals (maximum delegation)

They write, “Your employees can exercise five levels of initiative in handling on-the-job problems. From lowest to highest, the levels are:

•Wait until told what to do.

• Ask what to do.

• Recommend an action, and then with your approval, implement it.

• Take independent action, but advise you at once.

•Take independent action and update you through routine procedure.”

Symposium literature suggests another way to empower people: provide information. Everyone has heard the expression “Give a man a fish, he can eat for a day; teach a man to fish, he can eat for a lifetime.” To be more precise, we should say that if you teach a person to fish (the information transfer) and that person realizes the potential of this new ability, that person can eat for a lifetime.

The realization that fish are edible might be the person’s eureka moment. The distinction between teaching the mechanics of fishing and transferring the concept of fishing is subtle, but critical. The person who drops a hook in the water might catch fish occasionally, just as a person who gets on bicycle occasionally might cover some distance; however, the first person is not a fisherman and the second is not a bicyclist.

Besides delegating authority or providing information, there are other answers to our empowerment inquiry, such as providing the resources necessary to accomplish some objective or creating a safe environment to work, and let’s not forget constructive feedback and criticism.

An engineer who designs safety features into a Formula 1 car empowers the driver to go fast, without being overly concerned about safety. The driver is empowered by making the connection between the safety features and the opportunity to push the car faster.

A coach who analyzes a play so that the quarterback begins to see all of the elements of an unfolding play as a whole rather than as a set of separate actions and activities empowers the quarterback to see and seize opportunities while another quarterback is still thinking about what to do (and getting sacked).

These answers have some things in common:

Whether the actions or information is empowering is not inherent in those actions or the information. We know that because exactly the same actions, the same information, and the same methodologies can result in empowerment or no empowerment. If empowerment were inherent in some action or information, empowerment would result every time the action was taken.

Empowerment may be a result of the action or process, but it is not a step to be taken.

While it is almost certainly true that you cannot empower someone who does not want to be empowered, it is equally true that the willingness and desire to be empowered does not guarantee that empowerment will result from an interaction.

Now let’s talk about one more approach to empowerment. I had a mentor early in my career who liked to start coaching sessions by telling a joke. The setup for the joke was: “What does an American do when you ask him a question?” The punch line, “He answers it!”

Our teams reacted with dead silence. Our boss would assure us that the joke was considered very funny in Europe and that it was only our American culture that caused us to miss the punch line. Since he was the boss, we never argued. I’ve never tried the joke on my Russian friends, so I can’t confirm that they see the humor either.

The point, I think, was that Americans are culturally attuned to answers, not questions. Our game shows are about getting one right answer, first. Only Jeopardy, the television game show, pretends to care about the questions, but only as a gimmick.

When an employee experiences success and the boss asks about the approaches that worked when acknowledging that success, the boss is trying to empower that employee. The positive reinforcement and encouragement can cause the employee to go to look for the behaviors that contributed to that success and allow the employee to be successful in other areas. Empowerment comes when the employee takes a step back and finds an underlying behavior or way of looking at an issue or opportunity in the future.

Questions are especially empowering because they:

• Are non-threatening as opposed to direct statements

• Generate thought versus defense

• May lead to answers which neither the manager or the employee considered

•May lead to another question that empowers both you and your employee

• My presentation at the Symposium evolved as I prepared it. It was originally titled “Five Questions

Every Data Center Manager Should Ask Every Year.” As I have been working on using questions to

empower others (and myself) for a long time, the session was a great way for me to further that inquiry.

The five questions that I am currently living with are:

• Who am I preparing to take my job?

• How reliable does my data center need to be?

• What are the top 100 risks to my data center?

• What should my data center look like in 10 years?

• How do I know I am getting my job done?

And here are five questions that I have found to empower the people who work for me:

• What worked? In your recent success or accomplishment, what contributed to your success?

•What can I do as your boss to support your being more productive?

• What parts of your job are you ready to train others to do?

• What parts of my job would you like to take on?

• What training can we offer to make you more productive or prepare you to move up in our company?

These are examples of the kinds of inquiries that can be empowering, questions that you can ask yourself or someone else over and over again, possibly coming up with a different answer each time you ask. There may not be one right answer, and the inquiries maybe uncomfortable because they challenge what we already know.

G. Spencer Brown said, “To teach pride in knowledge is to put up an effective barrier against any advance upon what is already known, since it makes one ashamed to look beyond the bonds imposed by one’s ignorance.”

Whether your approach to empowering people goes through delegation, teaching, asking questions, or any of the other possible routes, keep in mind that the real aha moment comes from your commitment to the people who you want to empower. Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe said, “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative and creation, there is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings, and material assistance which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now.”

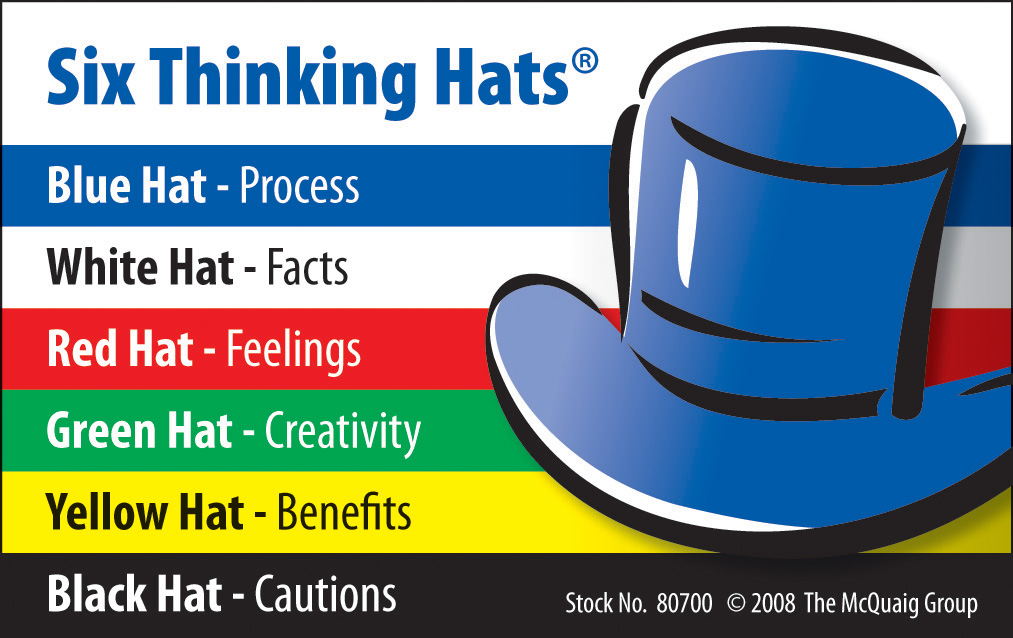

Six Thinking Hats

Well-known management consultant Edward de Bono wrote a book called Six Thinking Hats (Little, Brown and Company, 1985). His purpose was to empower people to resolve problems by giving them a mechanism to examine those problems in different ways—from different points of view. De Bono suggested that people imagine that they have six hats of different colors, with each hat representing a different approach or point of view to the problem.

The white hat calls for information known or needed. “The facts, just the facts.”

The yellow hat symbolizes brightness and optimism. Under this hat you explore the positives and probe for value and benefit.

The black hat is judgment, the devil’s advocate or why something may not work. Spot the difficulties and dangers; where things might go wrong. The black hat is probably the most powerful and useful of the hats but can be overused.

The red hat signifies feelings, hunches, and intuition. When using this hat you can express emotions and feelings and share fears, likes, dislikes, loves, and hates. The green hat focuses on creativity: the possibilities, alternatives, and new ideas. It’s an opportunity to express new concepts and new perceptions.

The blue hat is used to manage the thinking process. It’s the control mechanism that ensures the Six Thinking Hats guidelines are observed.

Fred Dickerman is vice president, Data Center Operations for DataSpace. In this role, Mr. Dickerman oversees all data center facility operations for DataSpace, a colocation data center owner/operator in Moscow, Russian Federation. He has more than 30 years experience in data center and mission-critical facility design, construction, and operation. His project resume includes owner representation and construction management for over US$1 billion in facilities development, including 500,000 square feet (ft2) of data center and 5 million ft2 of commercial properties. Prior to joining DataSpace, Mr. Dickerman was the VP of Engineering and Operations for a Colocation Data Center Development company in Silicon Valley.