Why data center operators are investing in more redundancy

When Uptime Institute recently asked over 300 data center managers how the pandemic would change their operations, one answer stood out: Two-thirds expect to increase the resiliency of their core data center(s) in the years ahead. Many said they expected their costs to increase as a result.

The reasoning is clear: the pandemic — or any future one — can mean operating with fewer staff, and possibly with disrupted service and supply chains. Remote monitoring and preventive maintenance will help to reduce the likelihood of an incident, but machines will always fail. It makes sense to reduce the impact of failure by increasing system redundancy.

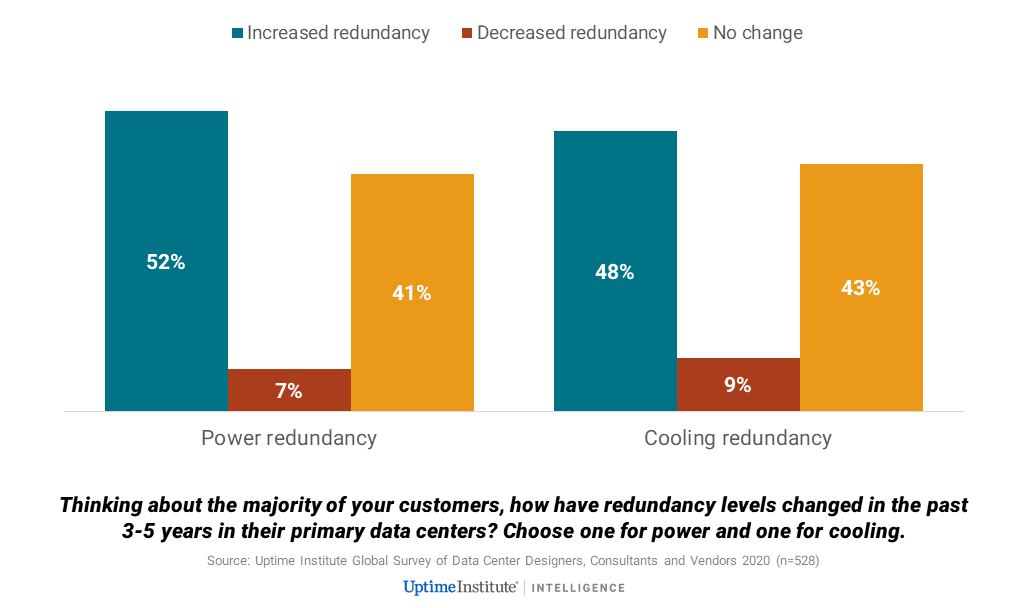

But even before the pandemic, there was a trend toward higher levels of redundancy. As shown in the figure below, roughly half of those participating in the Uptime Institute 2020 global survey of suppliers, designers and advisors reported their customers have increased redundancy levels in the last three to five years.

This trend may seem unsurprising to some, but it was not entirely predictable. The growth of cloud has been accompanied by the much greater use of multisite resiliency and regional availability zones. In theory, at least, these substantially reduce the impact of single-site facility outages, because traffic and workloads can be diverted elsewhere. Backed by this capability, some operators — Facebook is an example — have proceeded with lower levels of redundancy than was common in the past (thereby saving costs and energy).

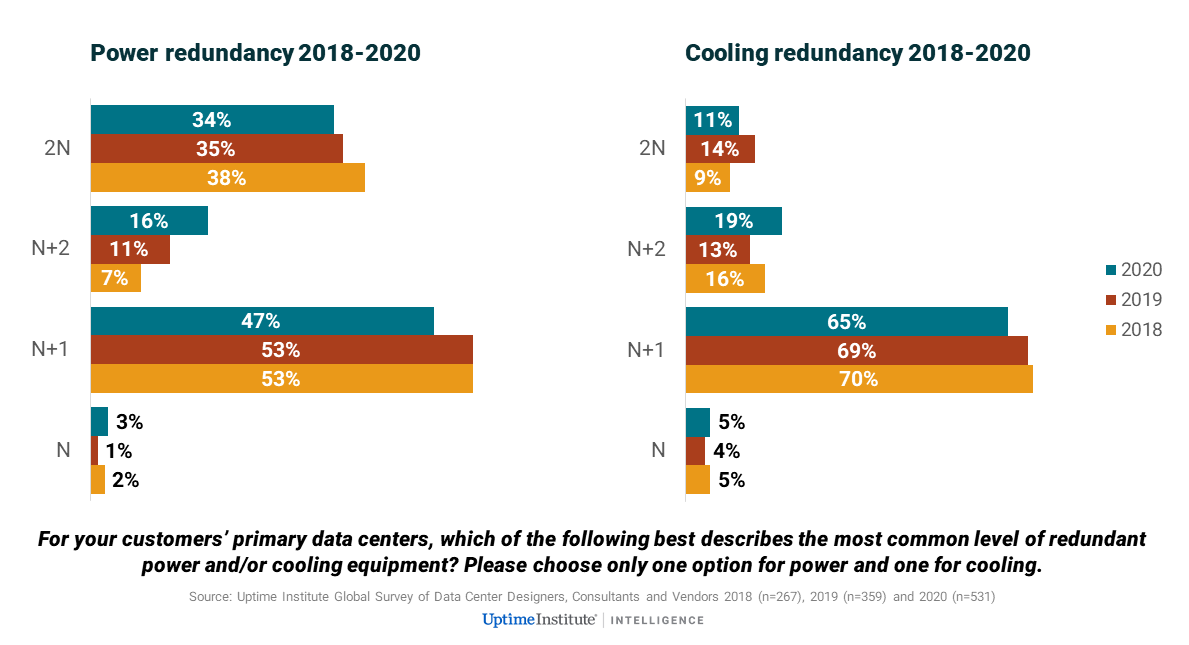

The use of availability zones, however, has come with its own problems, with networking and software issues often causing service interruptions. And the loss of one data center immediately places capacity and traffic demand on others, heightening risks. For this reason, even the big cloud providers and internet application operators manage mostly concurrently maintainable facilities, and it is common for them to stipulate that colocation partners have N+2 level facilities.

With a variety of options, the overall shift to increased resiliency is still slow and quite nuanced, with designers mostly favoring either N+1 or N+2 configurations, according to site and business needs, and, often, according to the creativity of the designers. Overall, there is actually a marginal decrease in the number of data centers that are 2N, but a steady three-year shift from N+1 to N+2 — not only in power, but also in cooling (see figure below). There is also an increase in the use of active-active availability zones, as discussed in our recent report Uptime Institute global data center survey 2020.

Demand patterns and growing IT dependency partly account for these higher levels of redundancy/resiliency. The level of resiliency needed for each service or by each customer is dictated by business requirements, but this is not fixed in time. The growing criticality of many IT services highlights the importance of mitigating risk through increased resiliency. “Creeping criticality” — a situation in which infrastructure and processes have not been upgraded or updated to reflect the growing criticality of the applications or business processes they support — may require redundancy upgrades.

Uptime Institute expects operators to make more use of distributed resiliency in the future — especially as more workloads are designed using cloud or microservices architectures (workloads are more portable, and instances are more easily copied). But there is no sign that this is diminishing the need for site-level resiliency. The software running these distributed services is often opaque, complex and may be prone to errors of programming or configuration. Annual outage data shows these types of issues are proliferating. Further, any big component failures can cascade, making recovery difficult and expensive, with data and applications synchronized across multiple sites.

The trend for now is clear: more resiliency at every level is the least risky approach — even if it means some extra expense and duplication of effort.

UI 2020

UI 2020 UI @ 2021

UI @ 2021

UI 2020

UI 2020

UI 2020

UI 2020