Higher data center costs unlikely to cause exodus to public cloud

A debate has been raging since cloud computing entered the mainstream: which is the cheaper venue for enterprise customers — cloud or on-premises data centers? This debate has proved futile for two reasons. First, the characteristics of any specific application will dictate which venue is more expensive — there is no simple, unequivocal answer. Second — the question implies that a buyer would choose a cloud or on-premises data center primarily because it is cheaper. This is not necessarily the case.

Infrastructure is not a commodity. Most users will not choose a venue purely because it costs less. Users might choose to keep workloads within their data centers or at a colo because they want to be confident they are fully compliant with legislation and / or regulatory requirements, or to be situated close to end users. They might choose cloud computing for workloads that require rapid scalability, or to access platform services further up the stack. Of course, costs matter to CIOs and CFOs alike, but cloud computing, on-premises data centers and colos all deliver value beyond their relative cost differences.

One way of assessing the value of a product is through a price-sensitivity analysis, whereby users are asked how they would (hypothetically) respond to price changes. Users who derive considerable value from a product are less likely to change their buying behavior following any increase in cost. Users more sensitive to cost increases will typically consider competing offers to reduce or maintain costs. Switching costs are also a factor in a user’s sensitivity to price changes. In cloud computing, for example, the cost of rearchitecting an application as part of a migration might not be justifiable if the resultant ongoing cost savings are limited.

IT decision-makers surveyed as part of Uptime Intelligence’s Data Center Capacity Trends Survey 2022 were asked what percentage of current workloads they would be likely to migrate to the cloud if their existing data center costs (covering on-premises and colos) rose 10%, 50% or 100%, respectively (assuming cloud prices remained stable).

While Uptime has neither conducted nor seen extensive research into rising costs, most operators are likely to be experiencing strong inflationary pressures (i.e., of over 15%) on their operations: energy prices and staff shortages being the main drivers.

The survey responses are illustrated in two different formats:

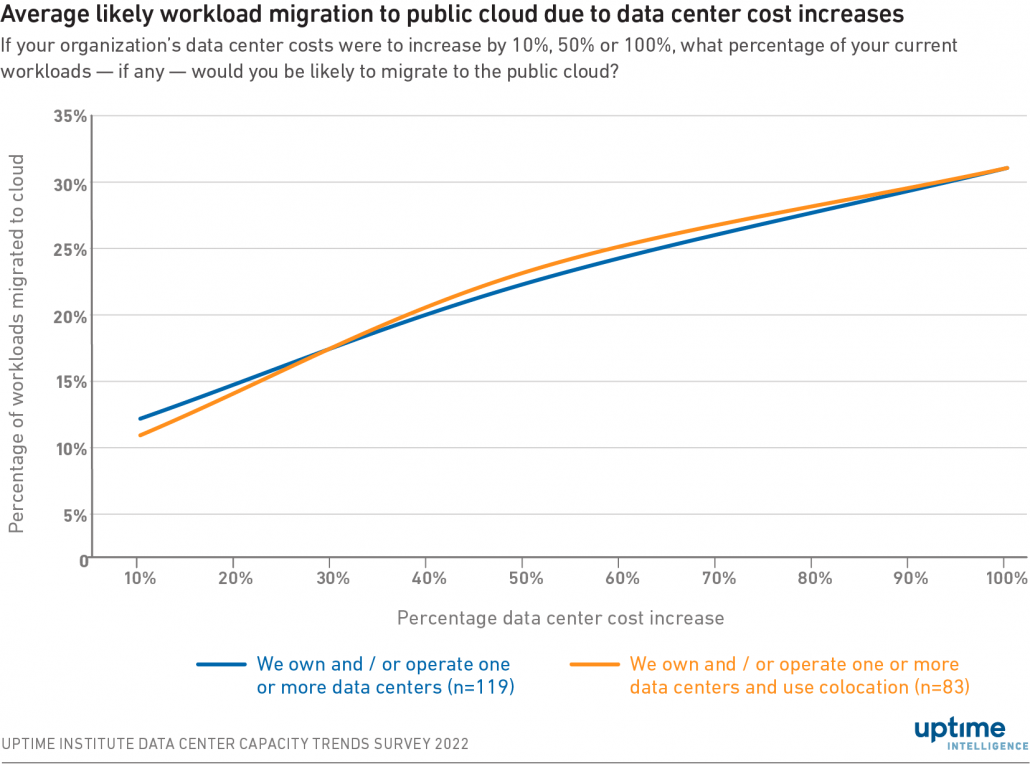

- Figure 1 summarizes the average percentage of workloads likely to be migrated to the cloud as a result of any increase in costs.

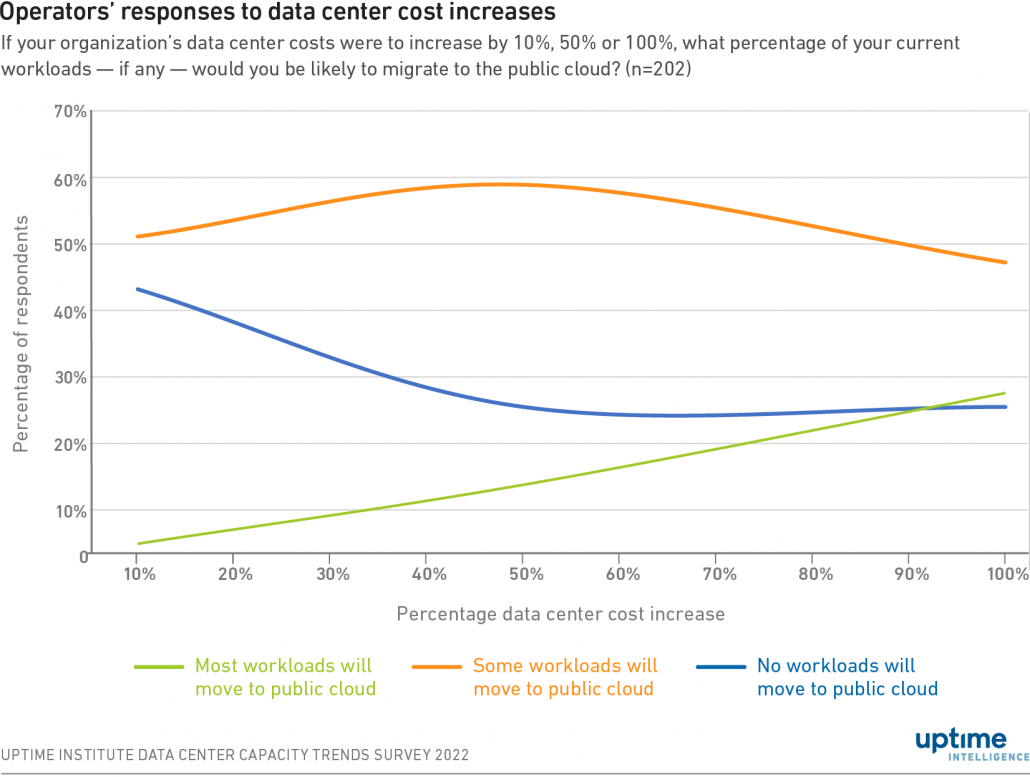

- Figure 2 shows what percentage of respondentswould make no response to any such increases (shown as 0%), what proportion would be likely to migrate some of their workloads (10% to 50%) and what proportion would be likely to migrate most of their workloads (50% or more).

What does this data tell us? Figure 1 shows that if on-premises or colo costs were to increase by 10%, then around 12% of workloads could migrate to the cloud. If costs were to increase by 50%, approximately 24% of workloads would potentially move to the cloud. Even if costs were to double, however, only just over 30% of workloads would be likely to migrate to the public cloud. This suggests that on-premises and colo users are not particularly price-sensitive. While they are likely to have some impact, rising data center costs per se are unlikely to trigger a mass exodus to the public cloud.

Some users are more price sensitive than others, however. Figure 2 shows that 42% of respondents indicate a 10% increase in costs would not drive any workloads to the public cloud. One quarter of respondents would still be unlikely to migrate workloads even if faced with price hikes of 50%. Notably, a quarter of respondents indicate they would not migrate any workloads even if costs were to double. This may suggest that at least 25% of those organizations surveyed do not consider the public cloud to be a viable option for their workloads currently.

This reluctance may be the result of several factors. Some respondents may derive value from hosting workloads in non-cloud data centers and may believe this to justify any additional expense. Others may believe that regulatory, technical and compliance issues render the public cloud unviable, making cost implications irrelevant. Some users may feel that moving to the public cloud is simply cost-prohibitive.

Most users are susceptible to price increases, however — at least to some extent. A 10% increase in costs would drive 55% of organizations to migrate some or most of their workloads to the cloud. A total of 59% of respondents indicate they would do so if faced with a more substantial 50% increase. Faced with a doubling of their costs, over a quarter of respondents would migrate most of their workloads to the cloud. Again, this is assuming that cloud costs remain constant — and it is unlikely that cloud providers could absorb such significant upward cost pressures without any increase in prices.

Other survey data (not shown in graphics) indicates that even if infrastructure expenditure were to double, only 7% of respondents would migrate their entire workloads to the cloud. Given that 25% of respondents indicate that they would keep all workloads on-premises regardless of cost increases, this confirms that most users are adopting a hybrid IT approach. Most users are willing to consider on-premises and cloud facilities for their workloads, choosing the most appropriate option for each application.

Although the Uptime Intelligence Data Center Capacity Trends Survey 2022 did not, specifically, cover the impact of price reductions, it is possible to estimate the potential impacts of cloud providers cutting their rates. A price cut of 10% would be unlikely to attract significantly more workloads to the public cloud: but a 50% reduction would have a more dramatic impact. As indicated above, however, cloud providers — faced with the same energy-cost challenges as data center owners and colos — are more likely to absorb any cost increases in their gross margins rather than risk damaging their credibility by raising prices (see OVHcloud price hike shows cloud’s vulnerability to energy costs).

In conclusion:

- Many organizations have no desire (or the ability) to use the public cloud, regardless of any cost increases, and will absorb any price hikes as best as they can.

- Most organizations are adopting a hybrid IT approach and use a mix of cloud and on-premises locations for their workloads.

- Rising costs (such as energy) may accelerate workload migration from on-premises data centers and colos to the public cloud (assuming cloud providers’ prices do not rise too).

- The costs involved in moving applications and rearchitecting them to work effectively in the public cloud mean single-digit cost increases are likely to have only a minimal effect on migrations.

- More significant cost increases could drive more workloads to the cloud since the savings to be made over the longer term could justify the switching costs involved.

- Public-cloud price reductions could, similarly, accelerate cloud migration; however, dramatic price cuts are unlikely.