The effects of a failing power grid in South Africa

European countries narrowly avoided an energy crisis in the past winter months, as a shortfall in fossil fuel supplies from Russia threatened to destabilize power grids across the region. This elevated level of risk to the normally robust European grid has not been seen for decades.

A combination of unseasonably mild weather, energy saving initiatives and alternative gas supplies averted a full-blown energy crisis, at least for now, although business and home consumers are paying a heavy price through high energy bills. The potential risk to the grid forced European data center operators to re-evaluate both their power arrangements and their relationship with the grid. Even without an energy security crisis, power systems elsewhere are becoming less reliable, including some of the major grid regions in the US.

Most mission-critical data centers are designed not to depend on the availability of an electrical utility, but to benefit from its lower power costs. On-site power generation — usually provided by diesel engine generators — is the most common option to backup electricity supplies, because it is under the facility operator’s direct control.

A mission-critical design objective of power autonomy, however, does not shield data center operators from problems that affect utility power systems. The reliability of the grid affects:

- The cost of powering the data center.

- How much diesel to buy and store.

- Maintenance schedules and costs.

- Cascading risks to facility operations.

South Africa provides a case study in how grid instability affects data center operations. The country has emerged as a regional data center hub over the past decade (largely due to its economic and infrastructure head-start over other major African countries), despite experiencing its own energy crisis over the past 16 years.

A total of 11 major subsea network cables land in South Africa, and its telecommunications infrastructure is the most developed on the continent. Although it cannot match the capacity of other global data center hubs, South Africa’s data center market is highly active — and is expanding (including recent investments by global colocation providers Digital Realty and Equinix). Cloud vendors already present in South Africa include Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, Huawei and Oracle, with Google Cloud joining soon. These organizations must contend with a notoriously unreliable grid.

Factors contributing to grid instability

Most of South Africa’s power grid is operated by state-owned Eskom, the largest producer of electricity in Africa. Years of under-investment in generation and transmission infrastructure have forced Eskom to impose periods of load-shedding — planned rolling blackouts based on a rotating schedule — since 2007.

Recent years have seen substation breakdowns, cost overruns, widespread theft of coal and diesel, industrial sabotage, multiple corruption scandals and a $5 billion government bail-out. Meanwhile, energy prices nearly tripled in real terms between 2007 and 2020.

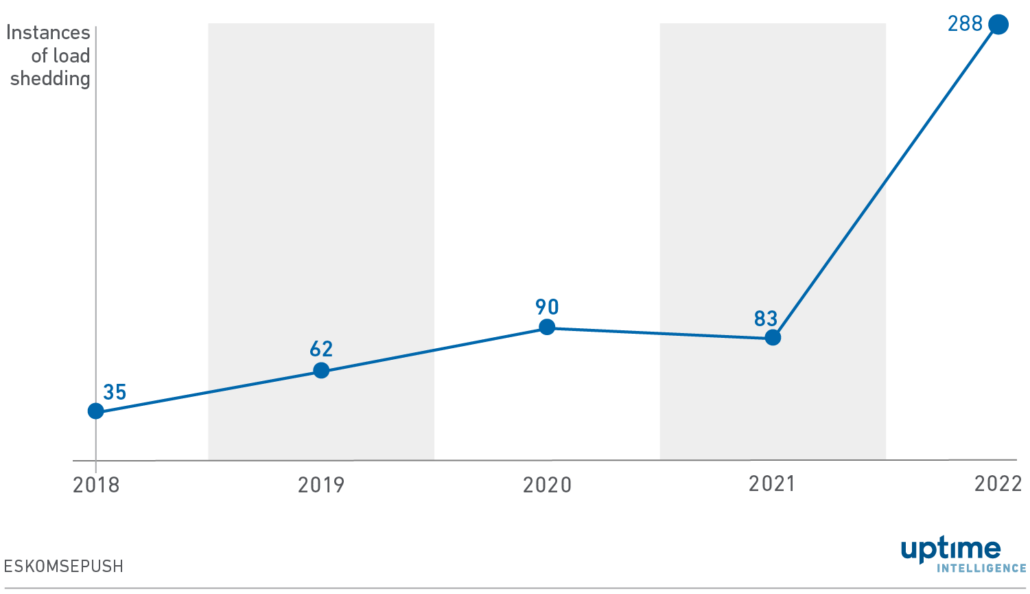

In 2022, the crisis deepened, with more power outages than in any of the previous 15 years — nearly 300 load-shedding events, which is three times the previous record of 2020 (Figure 1). Customers are usually notified about upcoming disruption through the EskomSePush (ESP) app. Eskom’s load-shedding measures do not distinguish between commercial and residential properties.

Blackouts normally last for several hours, and there can be several a day. Eskom’s app recorded at least 3,212 hours of load-shedding across South Africa’s grid in 2022. For more than 83 hours, South Africa’s grid remained in “Stage 6”, which means the grid was in a power shortfall of at least 6,000 megawatts. A new record was set in late February 2023, when the grid entered “Stage 8” load-shedding for the first time. Eskom has, in the past, estimated that in “Stage 8”, an average South African could expect to be supplied with power for only 12 hours a day.

Reliance on diesel

In this environment, many businesses depend on diesel generators as a source of power — including data centers, hospitals, factories, water treatment facilities, shopping centers and bank branches. This increased demand for generator sets, spare parts and fuel has led to supply shortages.

Load-shedding in South Africa often affects road signs and traffic lights, which means fuel deliveries are usually late. In addition, trucks often have to queue for hours to load fuel from refineries. As a result, most local data center operators have two or three fuel supply contracts, and some are expanding their on-site storage tanks to provide fuel for several days (as opposed to the 12-24 hours typical in Europe and the US).

There is also the cost of fuel. The general rule in South Africa is that generating power on-site costs about seven to eight times more than buying utility power. With increased runtime hours on generators, this quickly becomes a substantial expense compared with utility energy bills.

Running generators for prolonged periods accelerates wear and heightens the risk of mechanical failure, with the result that the generator units need to be serviced more often. As data center operations staff spend more time monitoring and servicing generators and fuel systems, other maintenance tasks are often deferred, which creates additional risks elsewhere in the facility.

To minimize the risk of downtime, some operators are adapting their facilities to accommodate temporary external generator set connections. This enables them to provision additional power capacity in four to five hours. One city, Johannesburg, has access to gas turbines as an alternative to diesel generators, but these are not available in other cities.

Even if the data center remains operational through frequent power cuts, its connectivity providers, which also rely on generators, may not. Mobile network towers, equipped with UPS systems and batteries, are frequently offline because they do not get enough time to recharge between load-shedding periods if there are several occurrences a day. MTN, one of the country’s largest network operators, had to deploy 2,000 generators to keep its towers online and is thought to be using more than 400,000 liters of fuel a month.

Frequent outages on the grid create another problem: cable theft. In one instance, a data center operator’s utility power did not return following a scheduled load-shedding. The copper cables leading to the facility were stolen by thieves, who used the load-shedding announcements to work out when it was safe to steal the cables.

Lessons for operators in Europe and beyond

- Frequent grid failures increase the cost of digital services and alter the terms of service level agreements.

- Grid issues may take years to emerge. The data center industry needs to be vigilant and respond to early warning signs.

- Data center operators must work with utilities, regulators and industry associations to shape the development of grids that power their facilities.

- Uptime’s view is that data center operators will find a way to meet demand — even in hostile environments.

Issues with the supply of Russian gas to Europe might be temporary, but there are other concerns for power grids around the world. In the US, an aging electricity transmission infrastructure — much of it built in the 1970s and 1980s — requires urgent modernization, which will cost billions of dollars. It is not clear who will foot this bill. Meanwhile, power outages across the US over the past six years have more than doubled compared with the previous six years, according to federal data.

While the scale of grid disruption seen in South Africa is extreme, it offers lessons on what happens when the grid destabilizes and how to mitigate those problems. An unstable grid will cause similar problems for data center operators around the world, and range from ballooning power costs to a higher risk of equipment failure. This risk will creep into other parts of the facility infrastructure if operations staff do not have time to perform the necessary maintenance tasks. Generators may be the primary source of data center power, but they are best used as an insurance policy.

2019

2019

2020

2020