Data shows the cloud goes where the money is

Hyperscale cloud providers have opened numerous operating regions in all corners of the world over the past decade. The three most prominent — Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure — now have 105 distinct regions (excluding government and edge locations) for customers to choose from to locate their applications and data. Over the next year, this will grow to 130 regions. Other large cloud providers such as IBM, Oracle and Alibaba are also expanding globally, and this trend is likely to continue.

Each region requires enormous investments in data centers, IT, software, people, and networks. The opening of a region may both develop and disrupt the digital infrastructure of the countries involved. This Update, part of Uptime Intelligence’s series of publications explaining and examining the development of the cloud, shows how investment can be tracked — and, to a degree, predicted — by looking at the size of the markets involved.

Providers use the term “region” to describe a geographical area containing a collection of independent availability zones (AZs), which are logical representations of data center facilities. A country may have many regions, with each region typically having two or three AZs. The three leading hyperscalers’ estates include more than 300 hyperscale AZs and many more data centers (including both hyperscale-owned and hyperscale-leased facilities) in operation today. Developers use AZs to build resilient applications in a single region.

The primary reason providers offer a range of regions is latency. In general, no matter how good the network infrastructure is, the further the end user is from the cloud application, the greater the delay and the poorer the end-user experience (especially on latency-sensitive applications, such as interactive gaming). Another important driver is that some cloud buyers are required to keep applications and user data in data centers in a specific jurisdiction for compliance, regulatory or governance reasons.

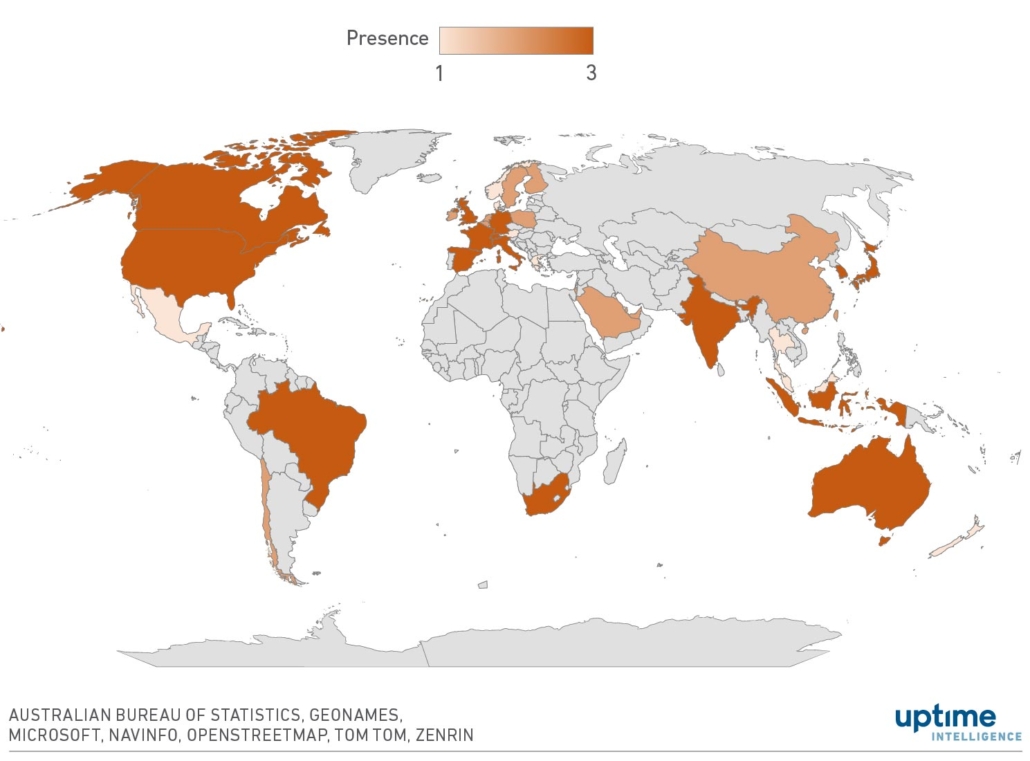

Figure 1 shows how many of the three largest cloud providers have regions in each country.

The economics of a hyperscale public cloud depends on scale. Implementing a cloud region of multiple AZs (and, therefore, data centers) requires substantial investment, even if it relies on colocation sites. Cloud providers need to expect enough return to justify such an investment.

To achieve this return on investment, a geographical region must have the telecommunications infrastructure to support the entire cloud region. Practically too, the location must be able to support the data center itself, and be able to provide reliable power, telecommunications, security and skills.

Considering these requirements, cloud providers focus their expansion plans on economies with the largest gross domestic product (GDP). GDP measures economic activity but, more generally, is an indicator of the health of an economy. Typically, countries with a high GDP have broad and capable telecommunications infrastructure, high technology skills, robust legal and contractual frameworks, and the supporting infrastructure and supply chains required for data center implementation and operation. Furthermore, organizations in countries with higher GDPs have greater spending power and access to borrowing. In other words, they have the cash to spend on cloud applications to give the provider a high enough return on investment.

The 17 countries where all three hyperscalers currently operate cloud regions, or plan to, account for 56% of global GDP. The GDP of countries where at least one hyperscaler intends to operate is 87% of global GDP across just 40 countries (for comparison, the United Nations comprises 195 countries).

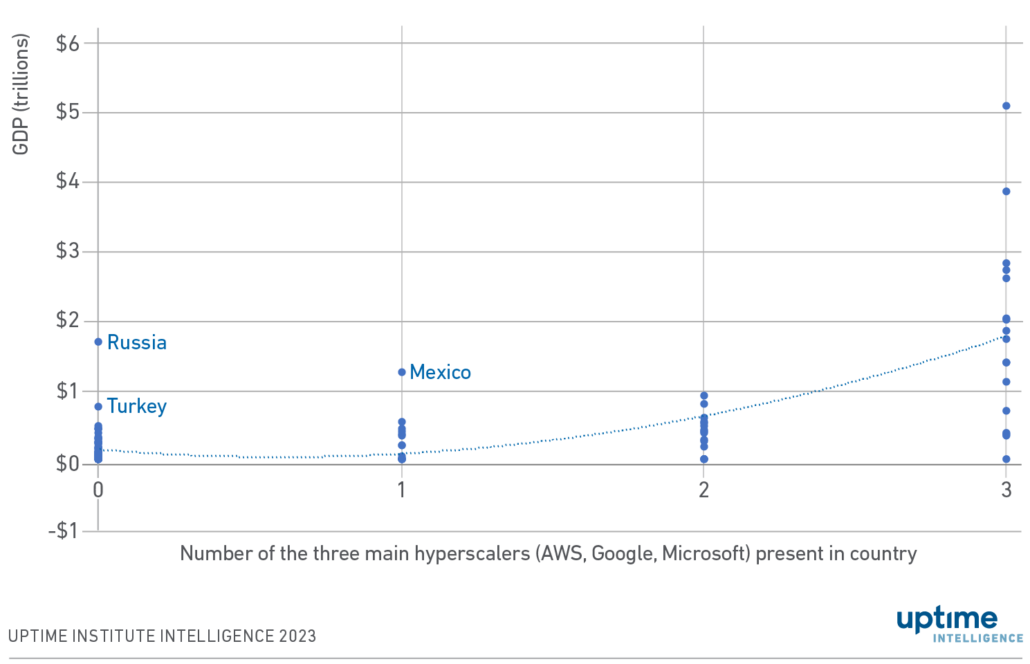

Figure 2 shows GDP against hyperscalers present in a country. (US and China’s GDPs are not shown because they are significant outliers.) The figure shows a trend: a greater GDP increases the likelihood of a hyperscaler presence in the region. Three countries buck this trend: Mexico, Turkey and Russia.

Observations

- The US is due to grow to 24 hyperscaler cloud regions across 13 states (excluding the US government), which is substantially more than any other country. This widespread presence is because Google, Microsoft and AWS are US companies with significant experience of operating in the country. The US is the single most influential and competitive market for digital services, with a shared official language, an abundance of available land, a business-friendly environment, and relatively few differences in regulatory requirements between local authorities.

- Despite China’s vast GDP, only two of the big three US hyperscalers operate there today: AWS and Microsoft Azure. However, unlike all other cloud regions, AWS and Microsoft regions are outsourced to Chinese companies to comply with local data protection requirements. AWS outsources its cloud regions to Sinnet and Ningxia Western Cloud Data Technology (NWCD); Azure outsources its cloud to 21Vianet. Notably, China’s cloud regions are totally isolated from all non-China cloud regions regarding connectivity, billing and governance. Google considered opening a China region in 2018 but abandoned the idea in 2020; one reason for this being a reluctance to operate through a partner, reportedly. China has its own hyperscaler clouds: Alibaba Cloud, Huawei Cloud, Tencent Cloud and Baidu AI Cloud. These hyperscalers have implemented regions beyond China and into greater Asia-Pacific, Europe, the US and the Middle East, primarily so that these China-based organizations can reach other markets.

- Mexico has a high GDP but only one cloud region, which Microsoft Azure is currently developing. Mexico’s proximity to the US and a good international telecommunications infrastructure means applications targeting Mexican users do not necessarily suffer significant latency. The success of the Mexico region will depend on the eventual price of cloud resources there. If Mexico does not offer substantially lower costs and higher revenues than nearby US regions (for example San Antonio in Texas, where Microsoft Azure operates), and if customers are not legally required to keep data local, Mexican users could be served from the US, despite minor latency effects and added network bandwidth costs. Uptime thinks other hyperscale cloud providers are unlikely to create new regions in Mexico in the next few years for this reason.

- Today, no multinational hyperscaler cloud provider offers a Russia region. This is unlikely to change soon because of sanctions imposed by a raft of countries since Russia invaded Ukraine. Cloud providers have historically steered clear of Russia because of geopolitical tensions with the US and Europe. Even before the Ukraine invasion, AWS had a policy of not working with the Russian government. Other hyperscalers, such as IBM, Oracle Cloud and China’s Alibaba, are also absent from Russia. The Russian Commonwealth of Independent States has no hyperscaler presence. Yandex is Russia’s most-used search engine and the country’s key cloud provider.

- A total of 16 European countries have either a current or planned hyperscaler presence and represent 70% of the continent’s GDP. Although latency is a driver, data protection is a more significant factor. European countries tend to have greater data protection requirements than the rest of the world, which drives the need to keep data within a jurisdiction.

- Turkey has a high GDP but no hyperscaler presence today. This is perhaps because the country can be served, with low latency, by nearby EU regions. Data governance concerns may also be a barrier to investment. However, Turkey may be a target for future cloud provider investment.

- Today, the three hyperscalers are only present in one African country, South Africa — even though Egypt and Nigeria have larger GDPs. Many applications aimed at a North African audience may be suitably located in Southern Europe with minimal latency. However, Nigeria could be a potential target for a future cloud. It has high GDP, good connectivity through several submarine cables, and would appeal to the central and western African markets.

- South American cloud regions were previously restricted to Brazil, but Google now has a Chilean region, and Azure has one in the works. Argentina and Chile have high relative GDP. It would not be surprising if AWS followed suit.

Conclusions

As discussed in Cloud scalability and resiliency from first principles, building applications across different cloud providers is challenging and costly. As a result, customers will seek cloud providers that operate in all the regions they want to reach. To meet this need, providers are following the money. Higher GDP generally equates to more resilient, stable economies, where companies are likely to invest and infrastructure is readily available. The current exception is Russia. High GDP countries yet to have a cloud presence include Turkey and Nigeria.

In practice, most organizations will be able to meet most of their international needs using hyperscaler cloud infrastructure. However, they need to carefully consider where they may want to host applications in the future. Their current provider may not support a target location, but migrating to a new provider that does is often not feasible. (A future Uptime Intelligence update will further explore specific gaps in cloud provider coverage.)

There is an alternative to building data centers or using colocation providers in regions without hyperscalers: organizations seeking new markets could consider where hyperscaler cloud providers may expand next. Rather than directly tracking market demand, software vendors may launch new services when a suitable region is brought online. The cost of duplicating an existing cloud application into a new region is small (especially compared with a new data center build or multi-cloud development). Sales and technical support can often be provided remotely without an expensive in-country presence.

Similarly, colocation providers can follow the money and consider the cloud providers’ expansion plans. A location such as Nigeria, with high GDP and no hyperscaler presence (but good telecommunications infrastructure) may be ideal for data center buildouts for future hyperscaler requirements.

Colocation providers also have opportunities outside the GDP leaders. Many organizations still need local data centers for compliance or regulatory reasons, or for peace of mind, even if a hyperscaler data center is relatively close in terms of latency. In the Uptime Institute Data Center Capacity Trends Survey 2022, 44% of 65 respondents said they would use their own data center if their preferred public cloud provider was unavailable in a country, and 29% said they would use a colocation provider.

Cloud providers increasingly offer private cloud appliances that can be installed in a customer’s data center and connected to the public cloud for a hybrid deployment (e.g., AWS Outposts, VMware, Microsoft Azure Stack). Colocation providers should consider if partnerships with hyperscaler cloud providers can support hybrid cloud implementations outside the locations where hyperscalers operate.

Cloud providers have no limits in terms of country or market. If they see an opportunity to make money, they will take it. But they need to see a return on their investment. Such returns are more likely where demand is high (often where GDP is high) and infrastructure is sufficient.

2019

2019