Accountability – the “new” imperative

Outsourcing the requirement to own and operate data center capacity is the cornerstone of many digital transformation strategies, with almost every large enterprise spreading their workloads across their own data centers, colocation sites and public cloud. But ask any regulator, any chief executive, any customer: You can’t outsource responsibility — for incidents, outages, security breaches or even, in the years ahead, carbon emissions.

Chief information officers, chief technology officers and other operational heads knew this three or four decades ago (and many have learned the hard way since). That is why data centers became physical and logical fortresses, and why almost every component and electrical circuit has some level of redundancy.

In 2021, senior executives will grapple with a new iteration of the accountability imperative. Even the most cautious enterprises now want to make more use of the public cloud, while the use of private clouds is enabling greater choices of third-party venue and IT architecture. But this creates a problem: cloud service operators, software-as-a-service (SaaS) providers and even some colos are rarely fully accountable or transparent about their shortcomings — and they certainly do not expect to be held financially accountable for consequences of failures. Investors, regulators, customers and partners, meanwhile, want more oversight, more transparency and, where possible, more accountability.

This is forcing many organizations to take a hard look at which workloads can be safely moved to the cloud and which cannot. For some, such as the European financial services sector, regulators will require an assessment of the criticality of workloads — a trend that is likely to spread and grow to other sectors over time. The most critical applications and services will either have to stay in-house, or enterprise executives will need to satisfy themselves and their regulators that these services are run well by a third-party provider, and that they have full visibility into the operational practices and technical infrastructure of their provider.

The data suggests this is a critical period in the development of IT governance. The shift of enterprise IT workloads from on-premises data center to cloud and hosted services is well underway. But there is a long way to go, and some of the issues around transparency and accountability have arisen only recently as more critical and sensitive data and functionality is considered for migration to the cloud.

The first tranche of workloads moving to third parties often did not include the most critical or sensitive services. For many organizations, a public cloud is (or was initially) the venue of choice for specific types of workloads, such as application test and development; big-data processing, such as AI; and new applications that are cloud-native. But as more IT departments become familiar with the tool sets from cloud providers, such as for application development and deployment orchestration, more types of workloads have moved into public clouds only recently, with more critical applications to follow (or perhaps not). High-profile, expensive public cloud outages, increased regulatory pressures and an increasingly uncertain macroeconomic outlook will force many enterprises to assess — or reassess — where workloads should actually be running (a process that has been called “The Big Sort”).

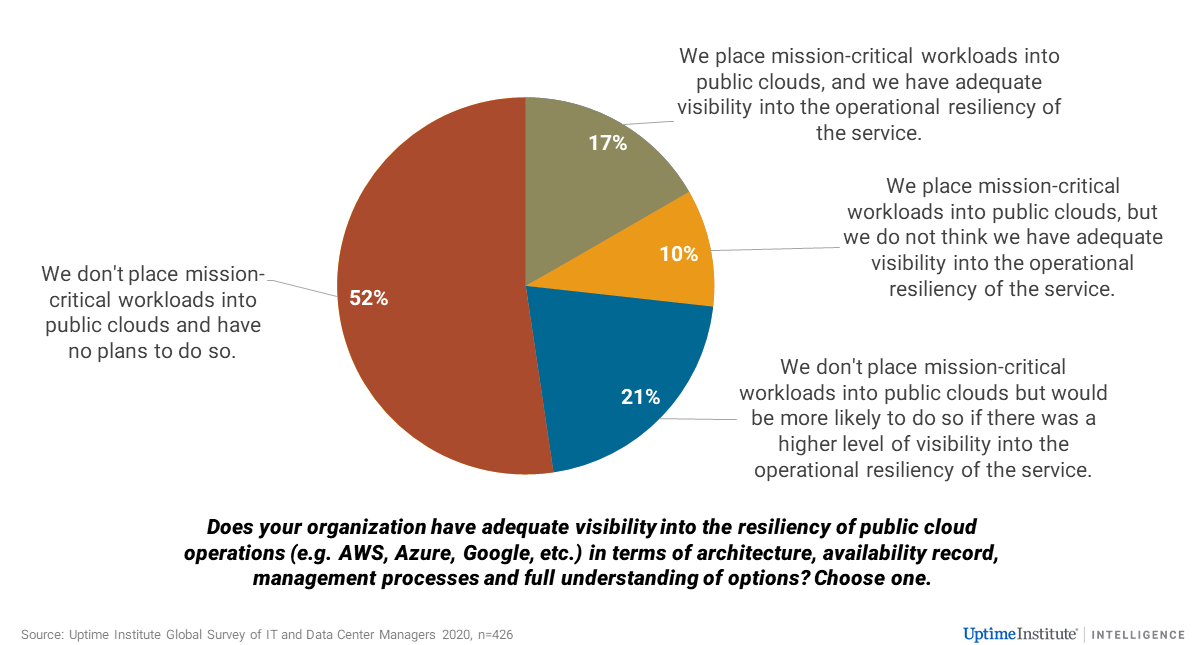

Uptime Institute believes that many mission-critical workloads are likely to remain in on-premises or colo data centers — at least for many years to come: More than 70% of IT and critical infrastructure operators we surveyed in 2020 do not put any critical workloads in a public cloud, with over a quarter of this group (21% of the total sample) saying the reason is a lack of visibility/accountability about resiliency. And over a third of those who do place critical applications in a public cloud also say they do not have enough visibility (see chart below). Clearly, providers’ assurances of availability and of adherence to best practices are not enough for mission-critical workloads. (These results were almost identical when we asked the same question in our 2019 annual survey.)

The issues of transparency, reporting and governance are likely to ripple through the cloud, SaaS and hosting industries, as customers seek assurances of excellence in operations — especially when financial penalties for failures by third parties are extremely light. While even the largest cloud and internet application providers operate mostly concurrently maintainable facilities, experience has shown that unaudited (“mark your own homework”) assurances frequently lead to poor outcomes.

Creeping criticality

There is an added complication. While the definitions and requirements of criticality in IT are dictated by business requirements, they are not fixed in time. Demand patterns and growing IT dependency mean many workloads/services have become more critical — but the infrastructure and processes supporting them may not have been updated (“creeping criticality”). This is a particular concern for workloads subject to regulatory compliance (“compliance drift”).

COVID-19 may have already caused a reassessment of the criticality or risk profile of IT; extreme weather may provide another. When Uptime Institute recently asked over 250 on-premises and colo data center managers how the pandemic would change their operations, two-thirds said they expect to increase the resiliency of their core data center(s) in the years ahead. Many said they expected their costs to increase as a result. One large public cloud company recently asked their leased data center providers to upgrade their facilities to N+1 redundancy, if they were not already.

But even before the pandemic, there was a trend toward higher levels of redundancy for on-premises data centers. There is also an increase in the use of active-active availability zones, especially as more workloads are designed using cloud or microservices architectures. Workloads are more portable, and instances are more easily copied than in the past. But we see no signs that this is diminishing the need for site-level resiliency.

Colos are well-positioned to provide both site-level resiliency (which is transparent and auditable) and outsourced IT services, such as hosted private clouds. We expect more colos will offer a wider range of IT services, in addition to interconnections, to meet the risk (and visibility) requirements of more mission-critical workloads. The industry, it seems, has concluded that more resiliency at every level is the least risky approach — even if it means some extra expense and duplication of effort.

Uptime Institute expects that the number of enterprise (privately owned/on-premises) data centers will continue to dwindle but that enterprise investment in site-level resiliency will increase (as will investment in data-driven operations). Data centers that remain in enterprise ownership will likely receive more investment and continue to be run to the highest standards.

The full report Five data center trends for 2021 is available to members of the Uptime Institute Inside Track community here.

UI @ 2020

UI @ 2020

UI @ 2020

UI @ 2020

UI 2020

UI 2020