Bring on regulations for data center sustainability, say Europe and APAC

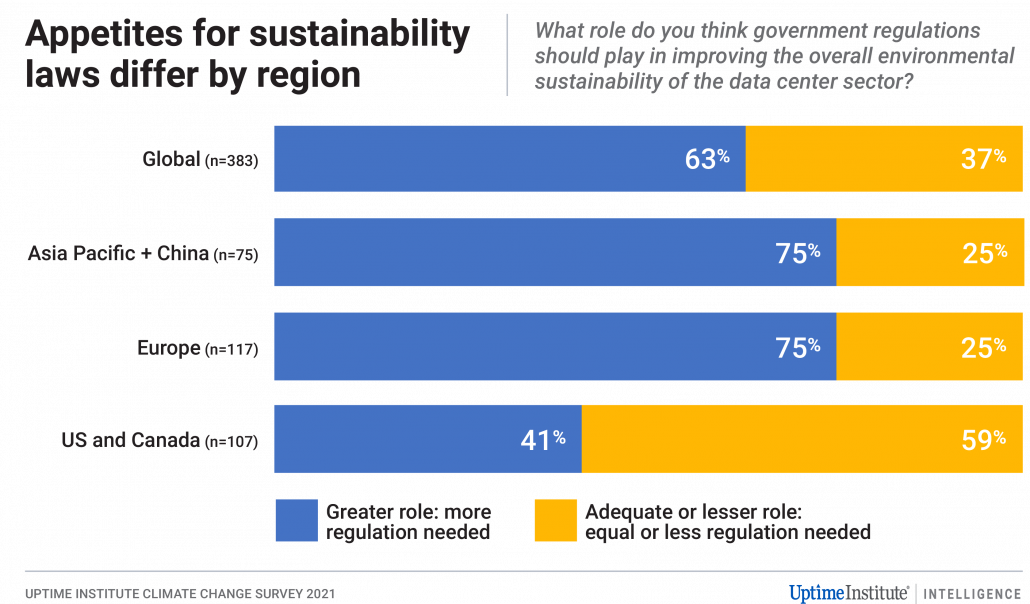

As the data center sector increases its focus on becoming more environmentally sustainable, regulators still have a part to play — the question is to what extent? In a recent Uptime Institute survey of nearly 400 data center operators and suppliers worldwide, a strong majority would favor regulators playing a greater role in improving the overall sustainability of data centers — except for respondents in North America.

Globally, more than three in five respondents favor greater reliance on statutory regulation. The strongest support (75% of respondents) is in Europe and APAC (Asia-Pacific, including China). However, in the US and Canada, fewer than half (41%) want more government involvement, with the majority of respondents saying the government plays an adequate role, or should play a lesser role, in sustainability regulation (See Figure 1).

Our survey did not delve into attitudes toward governments’ role in this area, but there are a few possible explanations for North America being an outlier. Globally, there is often a technical knowledge gap between industry professionals and government policymakers. As North America is the largest mature data center market, this gap may be more pronounced, fueling a general distrust by the sector toward legislators’ ability to create effective, meaningful laws. Indeed, North American participants have a lower opinion of their regulators’ understanding of data center matters compared with the rest of the world: four of 10 respondents rate their regulators as “not at all informed or knowledgeable.”

There are, however, cases of non-US legislation lacking technical merit, such as Amsterdam’s annual power usage effectiveness (PUE) limit of 1.2 for new data center builds. Although low PUEs are important, this legislation lacks nuance and does not factor in capacity changes — PUE tends to escalate at low utilization levels (for example, below 20% of the facility’s rated capacity). The requirement for a low PUE could incentivize behavior that is counterproductive to the regulation’s intent, such as enterprises and service providers moving (and leased operators commercially attracting) power-hungry applications to achieve a certain PUE number to avoid penalties. Also, these rules do not consider the energy efficiency of the IT.

Even if we accept the PUE’s limitations, the metric will likely have low utility as a regulatory dial in the future. Once a feature of state-of-the-art data centers, strong PUEs are now straightforward to achieve. Also, major technical shifts, such as the use of direct liquid cooling, may render PUE inconsequential. (See Does the spread of direct liquid cooling make PUE less relevant?)

The issue is not simply one of over-regulation: there are instances of legislators setting the bar too low. The industry-led Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact is a case in point. Formed in the EU, this self-regulatory agreement has signatory data center operators working toward reaching net-zero emissions by 2030 — 20 years earlier than the goal set by the EU government (as part of its European Green Deal).

Why, then, are most operators (outside of North America) receptive to more legislation? Perhaps it is because regulation, in some cases, benefitted the industry’s sustainability profile and received global attention as a reliable framework. Although Amsterdam’s one-year ban on new data center construction in 2019 was largely met with disapproval from the sector, it resulted in policies (including the PUE mandate) offering a clearer path toward sustainable development.

The new regulations for Amsterdam include designated campuses for new facility construction within the municipal zones, along with standards for improving the efficient use of land and raw materials. There are also regulations relating to heat re-use and multistory designs, where possible — all of which force the sector to explore efficient, sustainable siting, design and operational choices.

Amsterdam’s temporary ban on new facilities provided a global case study for the impacts of extreme regulatory measures on the industry’s environmental footprint. Similar growth-control measures are planned in Frankfurt, Germany and Singapore. If they realize benefits similar to those experienced in Amsterdam, support for regulation may increase in these regions.

In the grand scheme of sustainability and local impact, regulatory upgrades may have minimal effect. A clear policy, however, builds business confidence by removing uncertainty — which is a boon for data center developments with an investment horizon beyond 10 years. As for North America’s overall resistance, it could simply be that the US is more averse to government regulation, in general, than elsewhere in the world.

By: Jacqueline Davis, Research Analyst, Uptime Institute and Douglas Donnellan, Research Associate, Uptime Institute