Data center costs set to rise and rise

Up until two years ago, the cost of building and operating data centers had been falling reasonably steeply. Improving technology, greater production volumes as the industry expanded and consolidated, large-scale builds, prefabricated and modular construction techniques, stable energy prices and the low costs of capital have all played a part. While labor costs have risen during this time, better management, processes and automation have helped to prevent spiraling wage bills.

The past two years, however, have seen these trends come to a halt. Ongoing supply chain issues and rising labor, energy and capital costs all set to make building and running data centers more expensive in 2023 and beyond.

But the impact of these cost increases — affecting IT as well as facilities — will be muted due to the durable growth of the data center industry, fueled by global digitization and the overwhelming appetite for more IT. In response, most large data center operators (and data center capacity buyers) are continuing to move forward with expansion projects and taking on more space.

Smaller and medium-sized data center operators, however, that lack the resources to weather higher costs are likely to find this particularly challenging, with some smaller colocation operators (and enterprise data centers) struggling to remain competitive. Increasing overhead costs arising from new regulatory requirements and climbing interest rates will further challenge some operators, but an immediate rush to the public cloud is unlikely since this strategy, too, has non-trivial (and often high) costs.

Capital costs

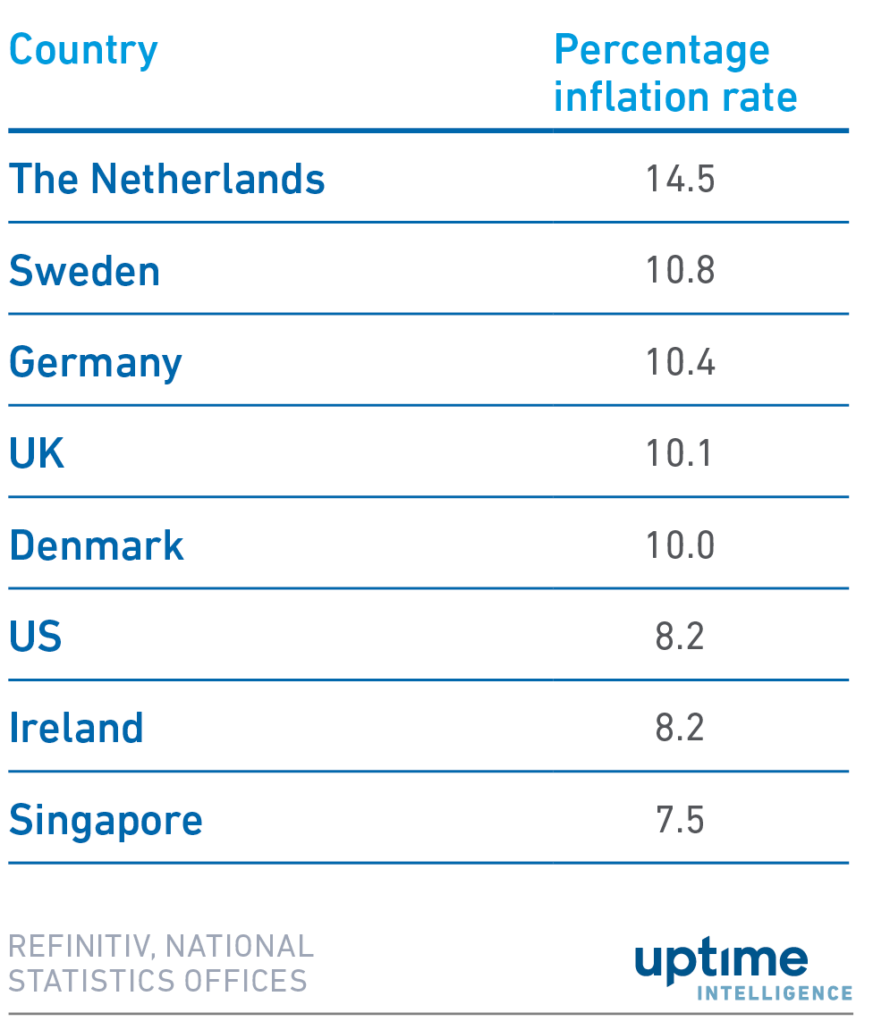

Capital plays a major part in the data center life cycle costing. Capital has been both cheap and readily available to data center builders for more than a decade: but the market changed in 2022. Countries that are home to major data center markets or to major companies that own and build data centers are now facing decades-high inflation rates (see Table 1), making it more difficult and more expensive to raise capital. But with increasing demand for capacity, partly due to a pent-up demand resulting from construction bottlenecks during the COVID-19 pandemic along with permitting and energy supply problems more recently, the most active and best positioned operators are funding their capacity expansion.

Uptime Institute’s Data Center and IT Spending Survey 2022 shows that more than two-thirds of enterprise and colocation operators expect to spend more in data center costs in 2023. Most enterprise data centers (90%) say they will be adding IT or data center capacity over the next two to three years, with half expecting to construct new facilities (although they may be closing down others).

The recent rise in construction costs may have come as a shock to some. Data center construction costs and lead-times had improved significantly in the 2010s, but we are now seeing a reversal of this trend. An average Tier III enterprise data center (a technical facility with concurrently maintainable site infrastructure) would have cost approximately $12 million per megawatt (MW) in 2010 per Uptime’s estimates (not including land and civil works) and would have taken up to two years to build.

Changes in design and construction had resulted in these costs dropping — in the best cases, to as little as $6 to $8 million per MW immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, with lead-times cut to less than 12 months. While Uptime has not verified these claims, some projects were reported to have been budgeted at less than $4 million per MW and taken just six months to complete.

The view today is markedly different. Long waiting times for some significant components (such as certain engine generators and centralized UPS systems) are driving up prices. By 2022, costs for Tier III specifications had risen by $1 million to $2 million per MW according to Uptime’s estimates. Lead-times can now reach or exceed 12 months, prolonging capacity expansion and refurbishment projects — and sometimes preventing operators from earning revenue from near complete facilities.

While prices for some construction materials have started to stabilize at an elevated level since the COVID-19 pandemic, prices are expected to increase further in 2023. Product shortages, together with higher prices for labor, semiconductors and power, are all having an inflationary effect across the industry. Concurrently, site acquisitions at major data center hubs with low-latency network connections now come at a premium, as popular data center locations run out of suitable land and power.

Uptime Institute’s Supply Chain Survey 2022 shows computer room cooling units, UPS systems and power distribution components to be the data center equipment most severely impacted by shortages. Of the 678 respondents to this survey, 80% said suppliers had increased their prices over the past 18 months. Notably, Li-ion battery prices, which had been trending downwards every year until 2021, increased in 2022 due to shortages of raw materials coupled with high demand.

More stringent sustainability requirements, too, contribute to higher capital costs. Regulations in some major data center hubs (such as Amsterdam and Singapore) mean only developments with highly energy efficient designs can move forward. But meeting these requirements will come at a cost (engineering fees, structural changes, different cooling systems), lifting the barriers to entry. New energy efficiency standards (as stipulated under the EC’s Energy Efficiency Directive recast, for example) will stress budgets still further (see Critical regulation: the EU Energy Efficiency Directive recast).

Operators are looking to recover the cost of sustainability requirements through efficiency gains. Surging power costs, which are likely to remain high in the coming years, now mean the calculation has shifted in favor of more aggressive energy optimization — but upfront capital requirements will often be higher.

Operating and IT costs

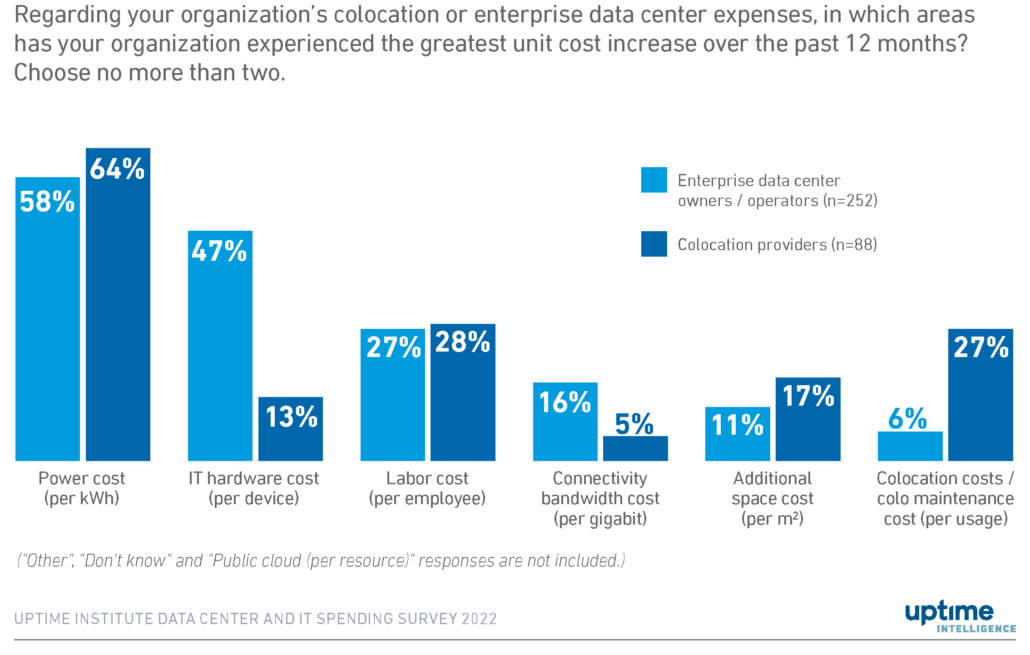

The operating expenditures associated with data centers and IT infrastructure are also set to increase in 2023, due to steep rises in major input costs. Uptime Institute’s Data Center and IT Spending Survey 2022 showed power to be driving the greatest unit cost increases for most operators (see Figure 1) — the result of high gas prices, the transition to renewable energy, imbalances in grid supply and the war in Ukraine.

The UK and the EU have been most affected by these increases, with certain colocation operators passing down some significant increases in energy costs to their customers. While energy prices are expected to drop (at least against the record highs of 2022), they are likely to remain well above the average levels of the past two decades.

Second only to power, IT hardware showed the next greatest increase in unit costs for enterprise data center respondents, partly because of various dislocations in the hardware supply chain, shortages of some processors and switching silicon, and inflation. Demand for IT hardware has continued to outpace supply, and manufacturing backlogs resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have yet to catch up.

Uptime sees promising signs of improvements in data center hardware supply, largely due to a recent sag in global demand (caused by economic headwinds and IT investment cycles). As a result, prices and lead-times for generic IT hardware (with some exceptions) will likely moderate in the first half of 2023.

If history is any guide, demand for data center IT will rise again some time in 2023 once some major IT infrastructure buyers accelerate their capacity expansion, which will yet again lead to tightness in the supply of select hardware later in the year.

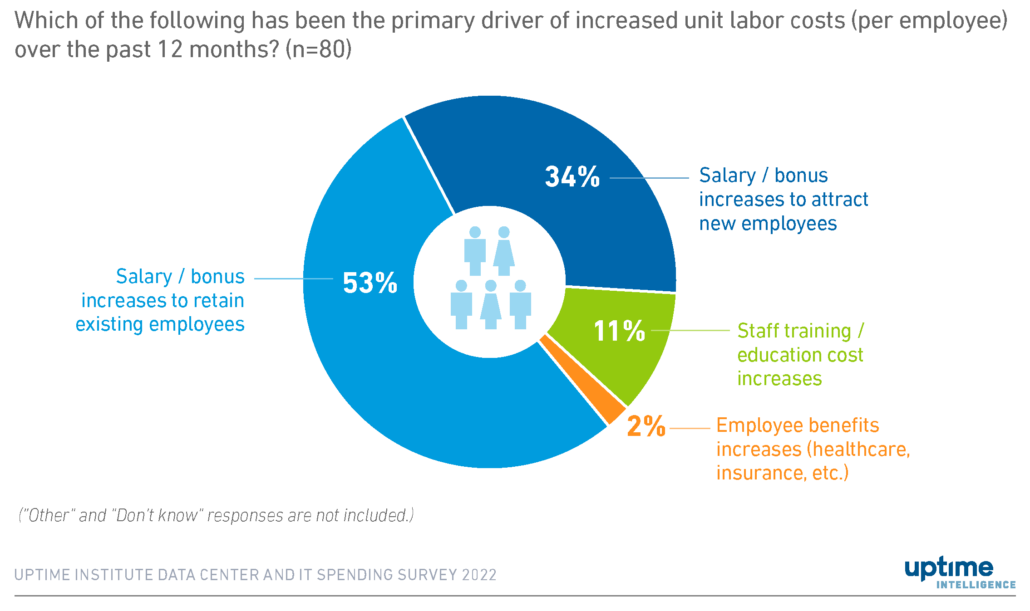

Staffing will also play a major role in the increased cost of running data centers, and is likely to continue to impact the industry beyond 2023. Many operators say they are spending more on labor costs in a bid to retain current staff (see Figure 2). This presents a further challenge for those enterprises that are unable to match salary offers made by some of the booming tech giants.

The aggregate view is clear: the overall costs of building and running data centers is set to rise significantly over the next few years. While businesses can deploy various strategies and technologies — such as automation, energy efficiency and tactical migration to the cloud — to reduce operational costs, these are likely to entail capital investment, new skills and technical complexity.

Will data centers becoming more expensive drive more operators towards colocation or the cloud? It seems unlikely that higher on-premises costs will cause greater migration per se. Results from Uptime Institute’s Data Center and IT Spending Survey 2022 show that despite increasing costs, many operators find that keeping workloads on-premises is still cheaper than colocation (54%, n=96) or migrating to the cloud (64%, n=84).

Estimating the costs of each of these options, however, is difficult in a rapidly changing market, in which some costs are opaque. Given the high costs associated with migrating to the cloud, it is likely to be cheaper for enterprises to endure higher construction and refurbishment costs in the near term and benefit from lower operating costs over the longer term. Not all companies will be able capitalize on this strategy, however.

Those larger organizations with the financial resources to benefit from economies of scale, with the ability to raise capital more easily and with sufficient purchasing power to leverage suppliers, are likely to have lower costs compared with smaller companies (and most enterprise data centers). Given their scale, however, they are still likely to face higher costs elsewhere, such as sustainability reporting and calls for proving — and improving — their infrastructure resiliency and security.

The full report Five data center predictions for 2023 is available to download here.

See our Five Data Center Predictions for 2023 webinar here.

Max Smolaks

Douglas Donnellan

2020

2020 Getty

Getty

UI @2021

UI @2021