High costs drive cloud repatriation, but impact is overstated

Unexpected costs are driving some data-heavy and legacy applications back from public-cloud to on-premises locations. However, very few organizations are moving away from the public cloud strategically — let alone altogether.

The past decade has seen numerous reports of so-called cloud “repatriations” — the migration of applications back to on-premises venues following negative experiences with, or unsuccessful migrations to, the public cloud. These reports have been cited by some colocation providers and private-cloud vendors as evidence of the public cloud’s failures, particularly concerning cost and performance.

Cloud-storage vendor Dropbox brought attention to this issue after migrating from Amazon Web Services (AWS) in 2017. Documents submitted to the US Securities Exchange Commission suggest the company saved an estimated $75 million over the next two years, as a result. Software vendor 37signals also made headlines after moving its project management platform Basecamp and email service Hey from AWS and Google Cloud to a colocation facility.

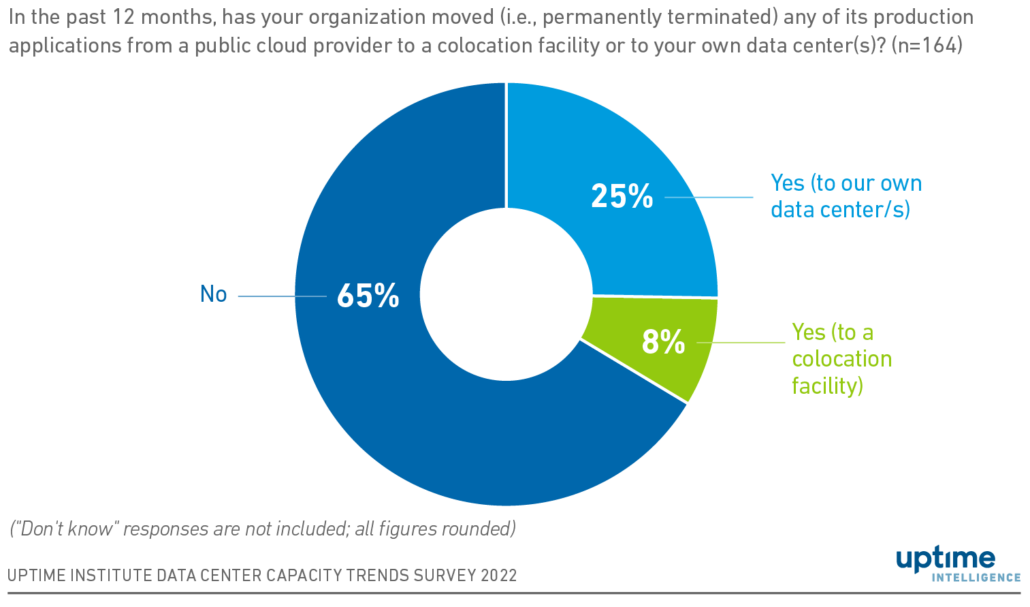

Responses to Uptime Institute’s 2022 Data Center Capacity Trends Survey also indicated that some applications are moving back to the public cloud. One-third (33%) of respondents said their organizations had moved production applications from a public-cloud provider to a colocation facility or data center on a permanent basis (Figure 1). The terms “permanently” and “production” were included in this survey question specifically to ensure that respondents did not consider applications being moved between venues due to application development processes or redistribution across hybrid-cloud deployments.

Poor planning for scale is driving repatriation

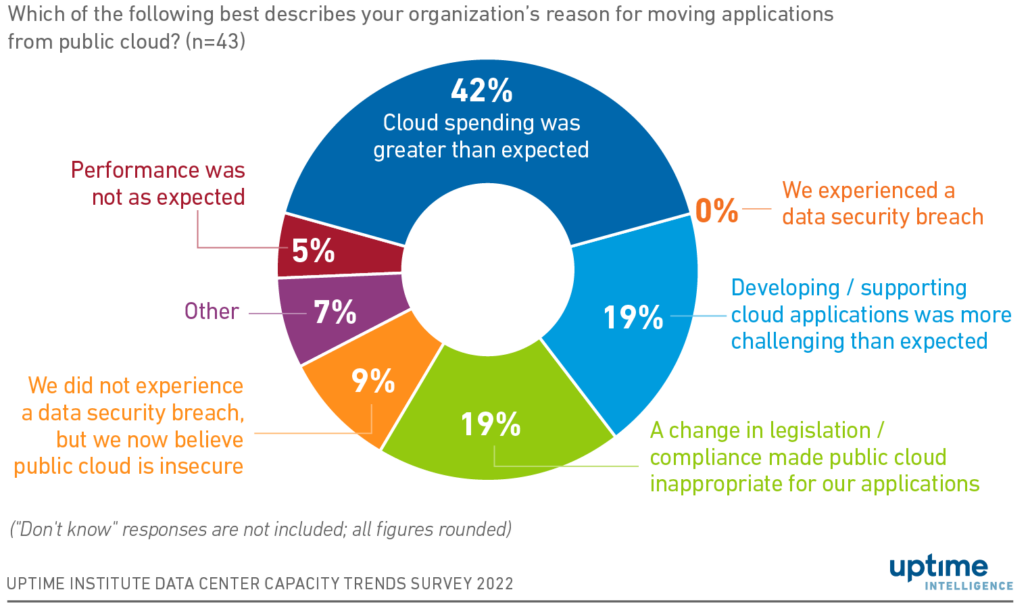

Respondents to Uptime Institute’s 2022 Data Center Capacity Trends Survey cited cost as the biggest driver behind migration back to on-premises facilities (Figure 2).

Why are costs greater than expected?

Data is often described as having “gravity” — meaning the greater the amount of data stored in a system the more data (and, very often, software applications) it will attract over time. This growth is logical in light of two major drivers: data growth and storage economics. Most users and applications accumulate more data automatically (and perhaps inadvertently) over time: cleaning and deleting data, on the other hand, is a far more manual and onerous (and, therefore, costly) task. At the same time, the economics of data storage promote centralization, largely driven by strong scale efficiencies arising from better storage management. Dropbox’s data-storage needs were always going to grow over time because it aggregated large volumes of consumer and business users — with each gradually storing more data with the service.

The key benefits of cloud computing is scalability — not just upwards during periods of high demand (to meet performance requirements), but also downwards when demand is low (to reduce expenditure). Dropbox cannot shrink its capacity easily, as its data has gravity. It cannot easily reduce costs by scaling back resources. Dropbox, moreover, as a collection of private file repositories, does not benefit from other cloud services (such as web-scale databases, machine learning or Internet of Things technologies) that might use this data. Dropbox needs ever-growing storage capacity — and very little else — from a cloud provider. At Dropbox’s level of scale, the company would inevitably save money by buying storage servers as required and adding them to its data centers.

Does this mean all data-heavy customers should avoid the public cloud?

No. Business value may be derived from using cloud services which use this growing data as a source. This value often justifies the expense of storing cloud data. For example, a colossal database of DNA sequences might create a significant monthly spend. But if a cloud analytics service (one that would otherwise be time consuming and costly to deploy privately) could use this data source to help create new drugs or treatments, the price would probably be worth paying.

Many companies will not have the scale of Dropbox to make on-premises infrastructure cost efficient in comparison with the public cloud. Companies with only a few servers’ worth of storage might not have the appetite (or the staff) to manage storage servers and data centers when they could, alternatively, upload data to the public cloud. However, the ever-growing cost of storage is by no means trivial, even for some smaller companies: 37signals’ main reason for leaving the public cloud was the cost of data storage — which the company stated was over $500,000 per year.

Other migrations away from the public cloud may be due to “lifting-and-shifting” existing applications (from on-premises environments to the public cloud) without rearchitecting these to be scalable. An application that can neither grow to meet demand, nor shrink to reduce costs, rarely benefits from deployment on the public cloud (see Cloud scalability and resiliency from first principles). According to Uptime Institute’s 2022 Data Center Capacity Trends Survey most applications (41%) that were migrated back to on-premises infrastructure were existing applications that had previously been lifted and shifted to the public cloud.

The extent of repatriation is exaggerated

Since Dropbox’s migration, many analyses of cloud repatriation (and the associated commentary) have assumed an all-or-nothing approach to public cloud, forgetting that a mixed approach is a viable option. Organizations have many applications. Some applications can be migrated to the public cloud and perform as expected at an affordable price; others may be less successful. Just because 34% of respondents have migrated someapplications back from the public cloud it does not, necessarily, mean the public cloud has universally failed at those organizations. Nor does it suggest that the public cloud is not a viable model for all applications.

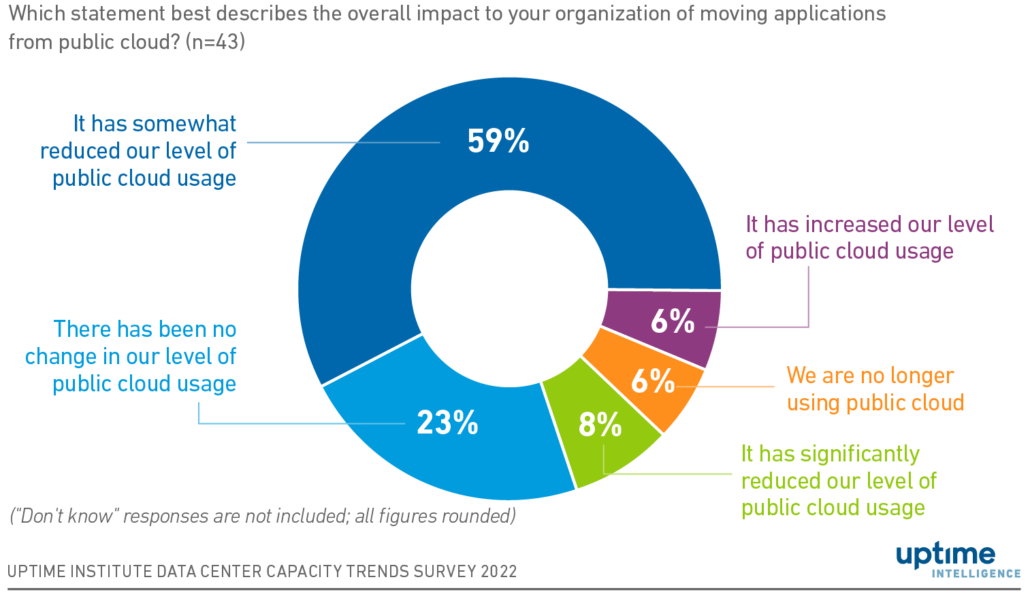

Only 6% of respondents to Uptime Institute’s 2022 Data Center Capacity Trends Survey stated that they had abandoned the public cloud altogether (Figure 3) due to cloud repatriation. Some 23% indicated that repatriation had no impact on public-cloud usage, with 59% indicating that cloud usage had been somewhat reduced by cloud adoption.

The low numbers of respondents abandoning public cloud suggests most are pursuing a hybrid approach, involving both on-premises and public-cloud venues. These venues don’t necessarily work together as an integrated platform. Hybrid IT here refers to an open-minded strategy regarding which venue is the best location for each application’s requirements.

Conclusion

Some applications are moving back to on-premises locations from the public cloud, with unexpected costs being the most significant driver here. These applications are likely to be slow-growing, data-heavy applications that don’t benefit from other cloud services, or applications that have been lifted and shifted without being refactored for scalability (upwards or downwards). The impact of repatriation on public-cloud adoption is, however, moderate at most. Some applications are moving away from the public cloud, but very few organizations are abandoning the public cloud altogether. Hybrid IT — at both on-premises and cloud venues — is the standard approach. Organizations need to thoroughly analyze the costs, risks and benefits of migrating to the public cloud before they move — not in retrospect.

Ui 2021

Ui 2021