Asset utilization drives cloud repatriation economics

The past decade has seen numerous reports of so-called cloud “repatriations” — the migration of applications back to on-premises venues following negative experiences with, or unsuccessful migrations to, the public cloud.

A recent Uptime Update (High costs drive cloud repatriation, but impact is overstated) examined why these migrations might occur. The Update revealed that unexpected costs were the primary reason for cloud repatriation, with the cost of data storage being a significant factor in driving expenditure.

Software vendor 37signals recently made headlines after moving its project management platform Basecamp and email service HEY from Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud to a colocation facility.

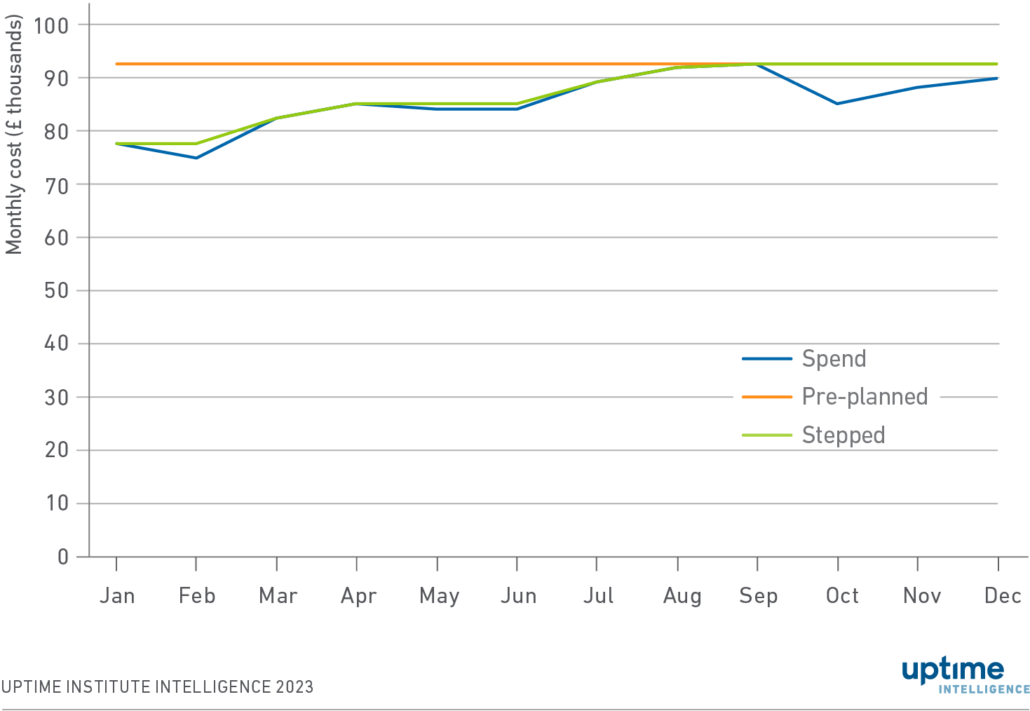

The company has published data on its monthly AWS bills for HEY (Figure 1). The blue line in Figure 1 shows the company’s monthly AWS expenditure. This Update examines this data to understand what lessons can be learned from 37signal’s experience.

37signals’ AWS spend — observations

Based on the spend charts included in 37signals’ blog (simplified in Figure 1), some observations stand out:

- The applications that are part of HEY scale proportionally. When database costs increase, for example, the cost of other services increases similarly. This proportionality suggests that applications (and the total resources used across various services) have been architected to scale upwards and downwards, as necessary. As HEY’s costs scale proportionally, it is reasonable to assume that costs are proportional to resources consumed.

- Costs (and therefore resource requirements) are relatively constant over the year — there are no dramatic increases or decreases from month to month.

- Database and search are substantial components of 37signals’ bills. The company’s database is not expanding, however, suggesting that the company is effective in preventing sprawl. 37signals’ data does not appear to have “gravity” — “gravity” here meaning the greater the amount of data stored in a system the more data (and, very often, software applications) it will attract over time.

While 37signals’ applications are architected to scale upwards and downwards as necessary, these applications rarely need to scale rapidly to address unexpected demand. This consistency allows 37signals to purchase servers that are likely to be utilized effectively over their life cycle without performance being impacted due to low capacity.

This high utilization level supports the company’s premise that — at least for its own specific use cases — on-premises infrastructure may be cheaper than public cloud.

Return on server investment

As with any capital investment, a server is expected to provide a return — either through increased revenue, or higher productivity. If a server has been purchased but is sitting unused on a data center floor, no value is being obtained, and CAPEX is not being recovered while that asset depreciates.

At the same time, there is a downside to using every server at its maximum capacity. If asset utilization is too high, there is nowhere for applications to scale up if needed. The lack of a capacity buffer could result in application downtime, frequent performance issues, and even lost revenue or productivity.

Suppose 37signals decided to buy all server hardware one year in advance, predicted its peak usage over the year precisely, and purchased enough IT to deliver that peak (shown in orange on Figure 1). Under this ideal scenario, the company would achieve a 98% utilization of its assets over that period (in a financial, not computing or data-storage sense) — that is, 98% of its investment would be used over the year for a value-adding activity.

The chance of the company being able to make such a perfect prediction is unlikely. Overestimating capacity requirements would result in lower utilization and, accordingly, more waste. Underestimating capacity requirements would result in performance issues. A more sensible approach would be to purchase servers as soon as required (shown in green on Figure 1). This strategy would achieve 92% utilization. In practice, however, the company would have more servers idle for immediate capacity, decreasing utilization further.

Cloud providers can never achieve such a high level of utilization (although non-guaranteed “spot” purchases can help). Their entire proposition relies on being able to deliver capacity when needed. As a result, cloud services must have servers available when required — and lots of them.

Why utilization matters

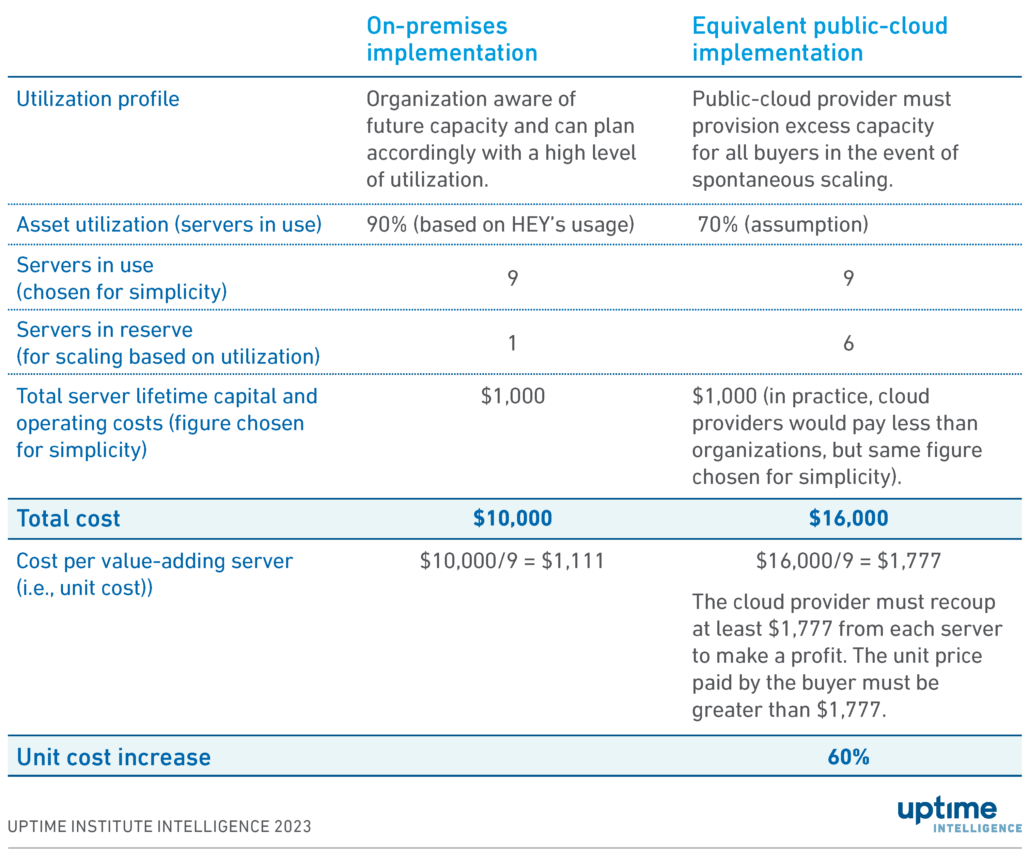

Table 1 makes simple assumptions that demonstrate the challenge a cloud provider faces in provisioning excess capacity.

These calculations show that this on-premises implementation costs $10,000 in total, with the cloud provider’s total costs being $16,000. Cloud buyers rent units of resources, however, with the price paid covering both operating costs (such as power), the resources being used, and the depreciating value (and costs) of servers held in reserve. A cloud buyer would pay a minimum of $1,777 per unit, compared with a unit cost of $1,111 in an on-premises venue. The exact figures are not directly relevant: what is relevant is the fact that the input cost using public cloud is 60% more per unit —purely because of utilization.

Of course, this calculation is a highly simplified explanation of a complex situation. But, in summary, the cloud provider is responsible for making sure capacity is readily available (whether this be servers, network equipment, data centers, or storage arrays) while ensuring sufficient utilization such that costs remain low. In an on-premises data center this balancing act is in the hands of the organization. If enterprise capacity requirements are stable or slow-growing, it can be easier to balance performance against cost.

Sustaining utilization

It is likely that 37signals has done its calculations and is confident that migration is the right move. Success in migration relies on several assumptions. Organizations considering migrating from the public cloud back to on-premises infrastructure are best placed to make a cost-saving when:

- There are unlikely to be sudden drops in resource requirements, such that on-premises servers are sitting idle and depreciating without adding value.

- Unexpected spikes in resource requirements (that would mean the company could not otherwise meet demand, and the user experience and performance would be impacted) are unlikely. An exception here would be if a decline in user experience and performance did not impact business value — for example, if capacity issues meant employees were unable to access their CEO’s blog simultaneously.

- Supply chains can deliver servers (and data center space) quickly in line with demand without the overheads involved in holding many additional servers (i.e., depreciating assets) in stock.

- Skills are available to manage those aspects of the infrastructure for which the cloud provider was previously responsible (e.g., MySQL, capacity planning). These factors have not been considered in this update.

The risk is that 37signals (or any other company moving back to the public cloud) might not be confident of these criteria being met in the longer term. Were the situation to change unexpectedly, the cost profile of on-premises versus public cloud can be substantially altered.

2019, Getty

2019, Getty