Building a data center facilities management team from scratch

The Dream Job

By Fred Dickerman

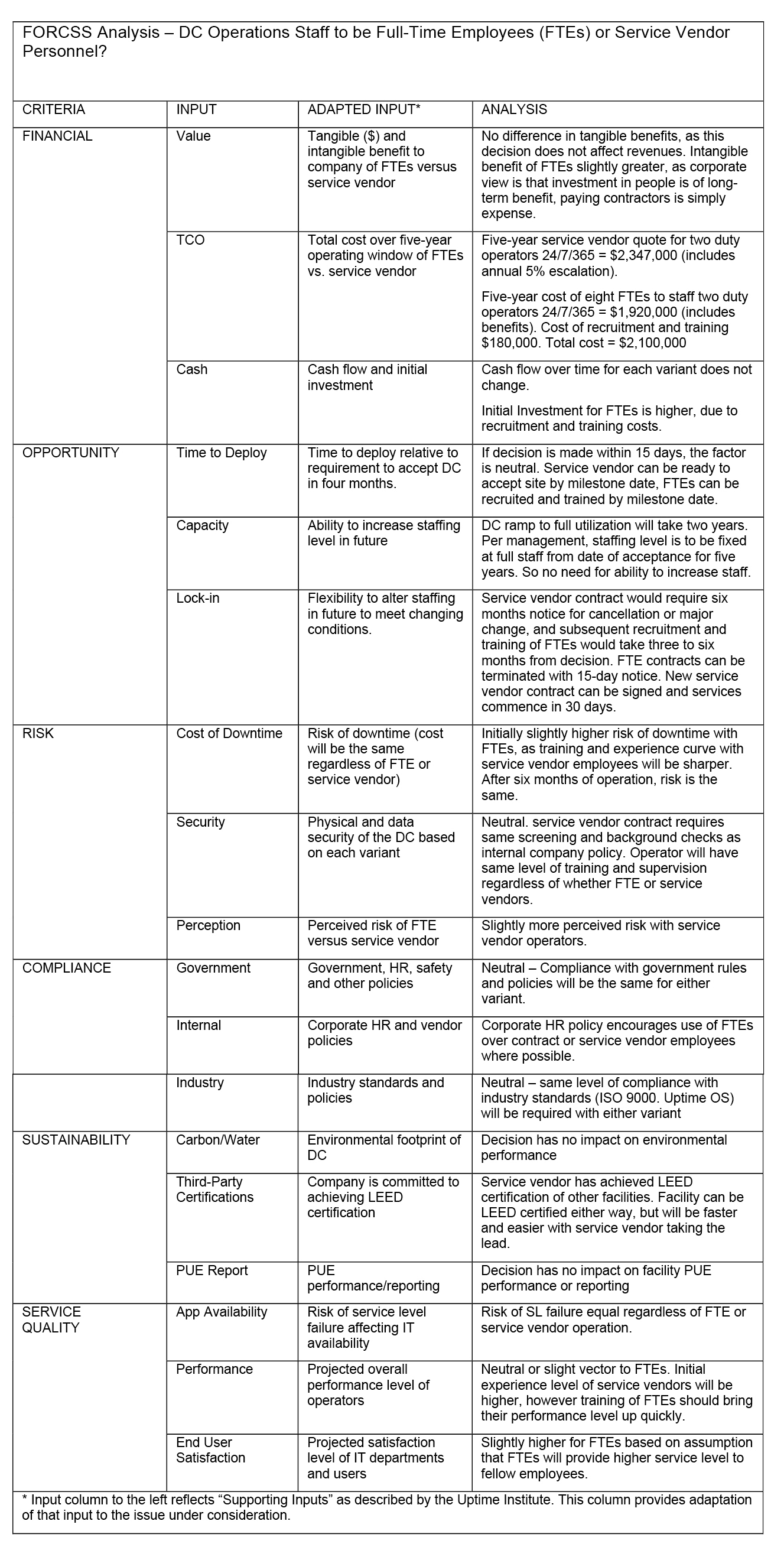

Editor’s note: Mr. Dickerman’s feature on the challenges of starting a Facilities Team breaks new and unexpected ground, as Mr. Dickerman adapts the new FORCSS methodology to help resolve a staffing question in a hypothetical case. The Uptime Institute did not anticipate this use of FORCSS as it developed the new methodology. In fact, records of the two Charrettes of industry stakeholders do not include any discussion of staffing levels.

Nonetheless, the Uptime Institute and the authors of the FORCSS document are gratified by Mr. Dickerman’s imaginative, if hypothetical, application of FORCSS, recognizing that the success of FORCSS as a tool depends on individuals like Mr. Dickerman finding it an easy-to-use tool to prioritize IT deployments.

It is Monday morning, and Pat, newly promoted to the position of Data Center program manager, is flying to the construction site of the company’s new data center. Last Friday the CIO of the company said to Pat, “I have good news and bad news! The good news is that based on the great job you did with the FORCSS™ analysis for our company’s five-year data center strategy, we have decided to promote you. You are going to be responsible for the operation of the new Tier III data center we’re building so we can consolidate all our IT into one facility.”

Naturally Pat wondered, “What’s the bad news?”

The CIO continued, “Since this is the first data center we’re going to own, we don’t actually have a Facility Management team for you to manage. You’re going to have to create the team starting from scratch. And the team has to be in place within four months to help commission the new data center and accept the facility from the contractor. Fly out to the site on Monday, and come back to me in two weeks with a draft of your plans for the new Facility Management team.”

Of course, some program managers, informed that they will be creating a Facility Management (FM) team from scratch, might view that as more good news rather than bad news.

Experienced facility managers will immediately recognize that Pat’s challenge is much bigger than just hiring a new FM team. The “People” component is certainly part of what needs to be done in the next four months; however, operating the new data center will also require establishing relationships with service vendors, utilities and suppliers. Creating a maintenance plan with tasks and schedules is essential, and each maintenance task, whether preventive, predictive or reactive, will require a written procedure for the operators to follow. In addition, the data center will need a complete set of operating policies and rules. While all this is being created, Pat (and the FM team) will need to monitor the construction of the new facility and participate in the commissioning, acceptance and certifications of the site. Finally, the FM team will want to establish a good working relationship with the team’s “customers,” the IT personnel who will be installing and operating IT equipment in the data center.

The Mission

Pat’s first task is to decide on a mission statement for the new FM team. Employees sometimes think of a mission statement as an enterprise-level declaration of the goals and objectives of a company, developed to have something to put on the first page of the annual report but having little relevance to operations. But all employees of an enterprise, and certainly all the managers, should have mission statements of their own, with three key elements:

- What am I supposed to do (goals and objectives)?

- Who am I supposed to do it for (clients/stakeholders)?

- How am I going to be measured (measures of value)?

In Pat’s case, the mission statement might start out quite simply:

Goals:

- Operate the data center with 100% safety and 100% availability. [In our story, Pat’s data center is a critical facility, with a consequent requirement for a commitment to 100% availability. An organization with several sites and a resilient overall architecture might, in theory, accept an objective of less than 100% availability, but it is hard to imagine any facility manager going to a CIO and saying “I’m committed to 95% uptime for this data center!”]

- Install and activate IT equipment as it migrates into the data center, on time and within budget.

- Manage the facility within an approved budget.

Clients/stakeholders:

- The CIO

- The company’s IT departments and IT users

- Stakeholders – The rest of the company, vendors, the company’s customers, shareholders.

Measures of value:

- Safety and availability records – no incidents, no events

- IT fit-out scheduled dates versus actual dates

- Facility budget versus actuals.

Of course, when Pat presents a mission statement to the CIO some additional objectives might be added:

- A PUE target

- A renewable energy target to support the company’s environmental sustainability goals

- Certification targets for the team to achieve Uptime Institute, ISO or other certifications within specified time frames.

Creating the Structure, and Structuring the Team

Once management has approved the mission of the new department, Pat can begin to develop the strategies required to reach the objectives. From this point forward all decisions will be based on the technical and business conditions specific to the new corporate data center, so Pat will need to understand those conditions. In addition to the obvious review of the design and equipment selections for the new data center, Pat will engage in in-depth discussions with all the IT user groups to understand their migration plans, capacity growth forecasts and the criticality of the applications that will be hosted in the data center.

Pat will also need to understand the exostructure–the external resources and factors that can either support or constrain the FM team or that pose a risk to the operation of the data center. [Note that IT departments sometimes refer to cloud-based services and other external IT resources as exostructure, but that is not how Pat’s company views it].

To understand the exostructure, Pat will need to interview key equipment vendors, local utilities and service providers to determine their capabilities, strengths and weaknesses and look at all the physical constraints and risks in the area. Finally, since almost all the decisions will result in some level of expenditure of company funds, Pat will want to carefully document everything learned during those investigations and the subsequent strategic decisions for inclusion in the budgeting process for the new department.

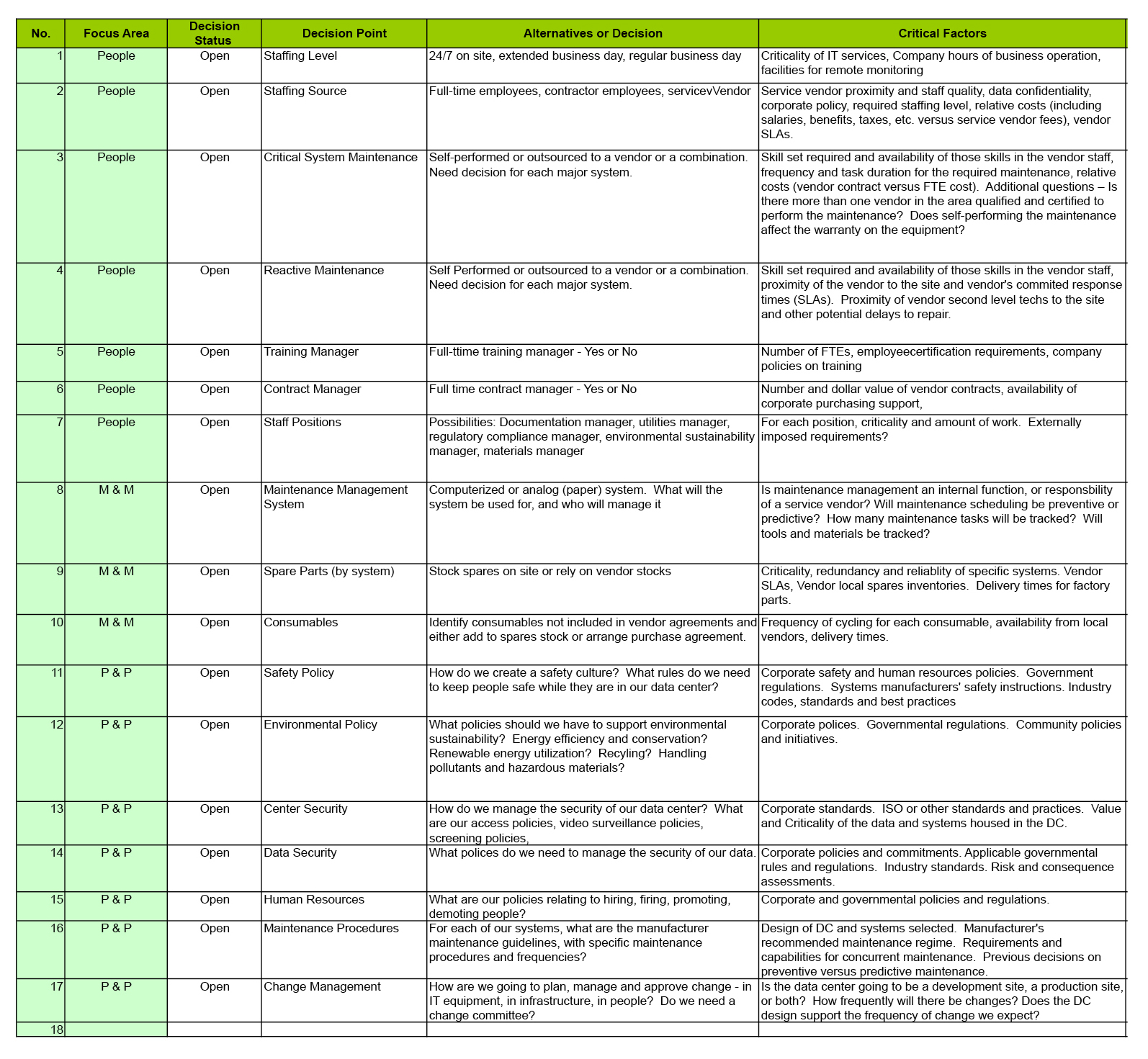

To develop strategies in a relatively simple manner, Pat might consider starting with three focus areas:

- People

- Materials and Methods (M&M)

- Policies and Procedures (P&P)

For each focus area, Pat must identify critical decision points; factors influencing each decision can be listed, perhaps in a simple spreadsheet or decision matrix as shown in Figure 1.

As Pat investigates the infrastructure and the exostructure specific to the new data center, the critical factors for each item can be replaced with real world data–costs, conditions, existing regulations or standards and so on. Then the decisions column can be filled in with Pat’s recommendations on each item. During the planning sessions with the CIO, the approval of those decisions can be documented.

The most significant decisions will require separate documentation, to explain the costs, risks and benefits of a particular issue (e.g. using FTEs or a service vendor to provide operations coverage after hours and on weekends or investing in a large inventory of spare parts on site).

Pat is comfortable with the FORCSS methodology and wants to make FORCSS a standard decision tool within the company. The more times the methodology is used in the decision process, the better. So, here’s how Pat might apply FORCSS to presenting one of the key decisions that needs to be made, justified and documented: whether to use FTEs or a service contractor for operational staffing of the new data center (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pat adapted FORCSS as a methodology to choose between a service vendor and in-house staffing.

The Facility Management Structure

After spending time going through the decision matrix and reviewing the FORCSS analyses of the major decisions with the CIO, Pat will be well positioned to assemble the facility management structure for the new data center.

The elements will include:

- The team’s mission statement with clear objectives and measurements. One of the objectives will be an internal service level agreement, essentially a contract between the FM team and the IT department, committing to availability, response and communication levels.

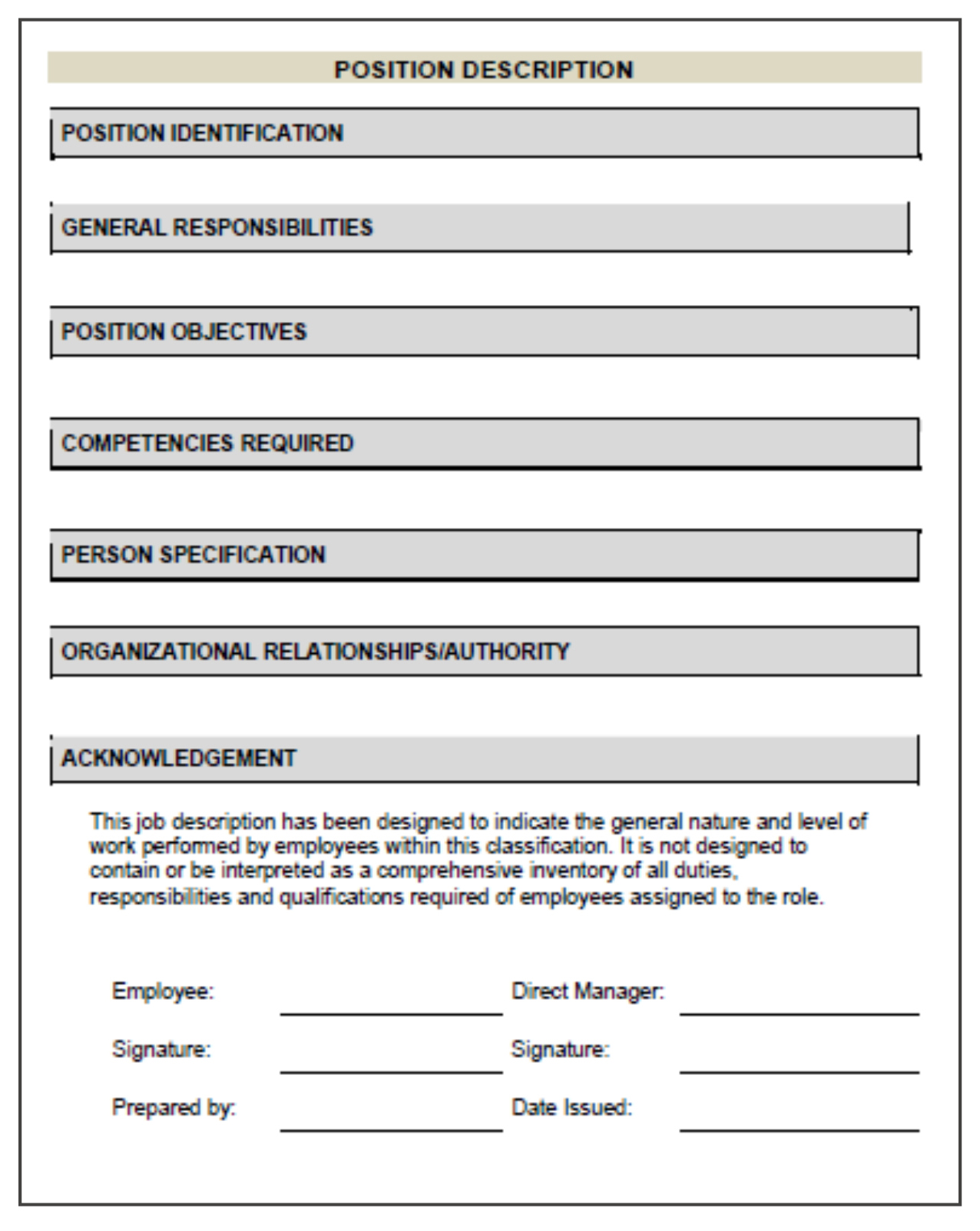

- A table of organization and responsibilities for the new department, including both internal positions and key vendors. For each internal position, there will be an associated job description; for each vendor, a scope description and service level agreement (see Figure 3).

- A staffing plan that details hours of operation, shift structures and tasks to be self-performed and outsourced. As this is a new data center, the staffing plan will include a recruiting plan to find and hire the employees required.

- A training plan with descriptions of each required training session and course, ranging from the safety overview session (SOS) given to every person who enters the data center to the individual development plans for full-time employees. Licenses, certifications or professional credentials required for any employee will be included in the training plan.

- A list of internal and external policies that will need to be created for the data center. This will include policies for safety, work rules, human resources, security and access, environmental sustainability, purchasing and materials management, cleaning and rules of conduct for employees, visitors and vendors.

- The vendor management plan, listing the vendors the FM team intends to contract with and ultimately detailing the scope of the vendor’s responsibilities and commitments, the service level agreement with that vendor, the vendor’s contacts and escalation, and the vendor’s freedom of action–tasks the vendor is allowed to do on a routine basis, tasks the vendor must ask permission to do and tasks the vendor must be supervised for.

- A list of the plans and procedures for preventive, predictive and reactive maintenance that will need to be created over the next four months. The procedures themselves can be developed based on manufacturer’s maintenance recommendations, industry standards, the design of the data center (including Tier level) and the framework of policies and rules that will regulate the operation of the data center.

- A description of the maintenance management system that the team will use to schedule, track and document preventive, predictive and reactive maintenance. This will include an acquisition plan to purchase the system and an implementation plan to place the system in operation, load the full list of maintenance tasks with associated tools, spares and consumables and a full set of operational procedures for using the system starting from Day 1.

- And since this is a new data center, Pat will include a commissioning and acceptance plan that will detail the steps in the transition from a site under construction to site in operation.

The last element of the facility-structuring plan that Pat will develop is a budget, which will have both capital expense and operating expense forecasts. Capital expenses in the first year will be high, since tools and equipment will need to be purchased, along with initial stocks of spares and consumables. Since Pat has carefully documented all the decisions that combine to create the facility management structure for the new data center, the operating budget can be derived from those decisions.

With a decision matrix and the outlines of the facility-structuring plan in hand, Pat is ready to meet with the CIO and get approval for these decisions and strategies. And once management has approved the plan, the hard work of turning that plan into reality can begin.

Timing

How much involvement the FM team has in the design, construction and commissioning of the site will affect the facility’s availability and hence the ability of the team to meet its mission statement, especially in the first days and weeks after a facility is accepted and handed over. Many of us have had experience with design engineers and skilled contractors who have never actually operated a critical facility, and who include elements in the infrastructure that will make the operations team’s task more difficult. Examples can range from mundane–valves that can only be reached by ladder or scissor lift, no convenience outlets in critical spaces to plug in tools–to silly–security doors with the magnetic lock on the unsecure side of the door, roof drains at the high point of a roof section–to serious–obstructed fire corridors and poorly positioned smoke detectors. And, commissioning agents usually test for reliability, not operability, so many of these operational snags will be missed during commissioning. And, at many new sites, commissioning tests (and sometimes Uptime Institute Tier Certification of Constructed Facility demonstrations) are performed by the contractor with the commissioning agent watching.

The FM team that will actually operate the facility may only be observing, not actively participating. So, the first time the facilities engineers take “hands-on” control of the systems is when the facility is in production.

The first time the critical systems’ maintenance tasks are performed is when the facility is in production. And, the first time the FM team must respond to a system or component failure is when the facility is in production.

It is understandable that owners may be reluctant to pay salaries or fees to an operations team with “nothing to operate” (while the facility is in design and construction), but having the FM team on site early on will reduce risk of human error during the critical first months of operation, when the site is at its most vulnerable. In addition, FM team involvement in the selection and purchase negotiations for major infrastructure systems should result in lower total cost of ownership (by reducing operational costs) as well as better documentation and training packages (two items which construction contractors seldom include in purchase negotiations, but which make a big impact on the operability of the site).

Fred Dickerman is vice president, Data Center Operations for DataSpace. In this role, Mr. Dickerman oversees all data center facility operations for DataSpace, a colocation data center owner/operator in Moscow, Russian Federation. He has more than 30 years experience in data center and missioncritical facility design, construction and operation. His project resume includes owner representation and construction management for over $1 billion (US) in facilities development, including 500,000 square feet of data center and five million square feet of commercial properties. Prior to joining DataSpace, Mr. Dickerman was the VP of Engineering and Operations for a Colocation Data Center Development company in Silicon Valley.

is vice president, Data Center Operations for DataSpace. In this role, Mr. Dickerman oversees all data center facility operations for DataSpace, a colocation data center owner/operator in Moscow, Russian Federation. He has more than 30 years experience in data center and missioncritical facility design, construction and operation. His project resume includes owner representation and construction management for over $1 billion (US) in facilities development, including 500,000 square feet of data center and five million square feet of commercial properties. Prior to joining DataSpace, Mr. Dickerman was the VP of Engineering and Operations for a Colocation Data Center Development company in Silicon Valley.